Church Background and Context

- Regional Background

This church is located geographically on the eastern boundary of the borough of Queens, New York City, adjacent to the western edge of Nassau County, New York. The boundaries of the area include Union Turnpike to the north, Francis Lewis Boulevard to the west, Murdock Avenue to the south, and Belt Parkway, Cross Island Parkway, and Winchester Boulevard to the east. The Grand Central Parkway, which connects to the Northern State Parkway, runs through the northern part of the neighborhood, as does the Long Island Expressway, making this location a major transportation hub between Long Island and New York City. The Clearview Expressway, which connects to the Throgs Neck Bridge leading to the Bronx and Connecticut, ends at Hillside Avenue in the northern corner of the neighborhood. The church itself is located just one block north of the well-known Jamaica Avenue and 220th Street, making it easy to find even for first-time visitors.

According to The Story of Queens Village (1), settlers from Connecticut arrived in the 1640s and settled in Hempstead. Around 20 families among them wanted to move westward, so they traded with the Native Americans for land between Hempstead and Canarsie in exchange for two guns, a coat, and some gunpowder and lead. On March 21, 1656, they settled in Jamaica (near Hawtree Creek, Lewis Boulevard, and 206th Street). On March 7, 1663, they purchased additional land from Native Americans between Spring Creek to the west (now the Brooklyn-Queens border) and Hook Creek to the east (now the Queens-Nassau border).

Queens Village slopes from a height of 200 feet above sea level along the Grand Central Parkway in the north to about 60 feet along Murdock Avenue in the south. While the plain stretching from western Queens to Wantagh was known as the “Great Plain,” Queens Village was known as the “Little Plain” until the 1600s (2). Because only coastal grass grew without any trees, a law was passed in the 1600s forbidding people from cutting grass before July 8 to ensure fodder for animals. In 1661, anyone who cut grass before August 10 had to pay a fine (3).

The church is part of the Queens Village administrative district in New York City. It belongs to Community Planning Board #13 and is within School District 29. The public schools in the area include one high school (grades 9–12), one middle school (grades 6–8), and four elementary schools (grades K–5). Private schools include one prep school (K–8), one Lutheran school (K–8), and two Catholic schools (K–8). Religious institutions include 3 Jewish synagogues, 3 Catholic churches, 1 Episcopal church, 3 Lutheran churches, 1 United Methodist Church, 1 Reformed Presbyterian church, 1 United Presbyterian church, 1 Korean church, 3 Baptist churches, and 1 Pentecostal church. There is also a YMCA, a library, a police precinct, and two post offices. The area is divided into three postal code zones: 11427, 11428, and 11429.

It is estimated that Queens Village became part of New York City’s administrative structure between 1898 and 1919 (4). According to the Queens County Times, a local newspaper published on September 23, 1971, the village was named Queens Village in 1685 in honor of Queen Catherine of Braganza, wife of King Charles II of England (5). The first post office was established in 1850, and the first school district was designated in 1857. A train station was established in 1871. In 1889, the village had its first fire department and firehouse. Telephones became publicly available in 1896, and trolleys began running along Jamaica Avenue in 1897. Electricity was introduced in 1898, and water supply from the city began in 1899. The subway arrived in 1905, and a city bus depot was built in 1924, with over 10 bus lines running through or terminating in the area. The first high school in the village was established in 1955 (6).

According to the 1980 census, the population of the village was 59,734. By 1989, it had grown to 60,680—a modest increase of 946 people over nine years. While overall growth has been slow, the population is changing due to the arrival of Indian, Filipino, and West Indian immigrants, who are replacing retiring and relocating white residents. Though population growth is moderate, the demographic makeup is shifting significantly toward minority groups. The number of households grew from 18,909 in 1980 to 20,447 in 1989, an increase of 1,538 households. This 16% growth is much lower than the global population growth rate of 1.72%, the U.S. growth rate of 9.8%, and New York State’s 2.5%, indicating a modest, steady growth. This increase is not due to natural births, but to the in-migration of minority populations such as Indians, Filipinos, and Jamaicans, significantly changing the area’s demographic composition.

Average household income rose from $23,217.67 to $38,873.67 over ten years—an increase of $15,656—showing that the village is home to a typical American middle-class population. The details of household income by ZIP code are as follows (7):

As shown in [Table 1], the average age has increased from 35.6 to 37.7, indicating an aging trend of 2.1 years. However, as seen in [Table 2], the areas where the church is located—zip codes 11427 and 11428—have significantly higher elderly populations (65 years and older), at 20.1% and 14%, respectively, compared to 9.7% in the 11429 area. Additionally, as [Table 3] shows, there is a racial contrast between these regions. In zip codes 11427 and 11428, where the church is located, White residents make up 76.8% and 75.7% of the population, respectively, whereas in 11429, Black residents make up 77.5%, revealing a stark racial difference within neighborhoods of the same village. The 11429 area, which begins just across the street to the south of Jamaica Avenue, one block from the church, is a region with a concentrated Black population.

The “Others” category, Table 3, is primarily composed of Indians, Filipinos, and a very small number of Chinese and Hispanic people.

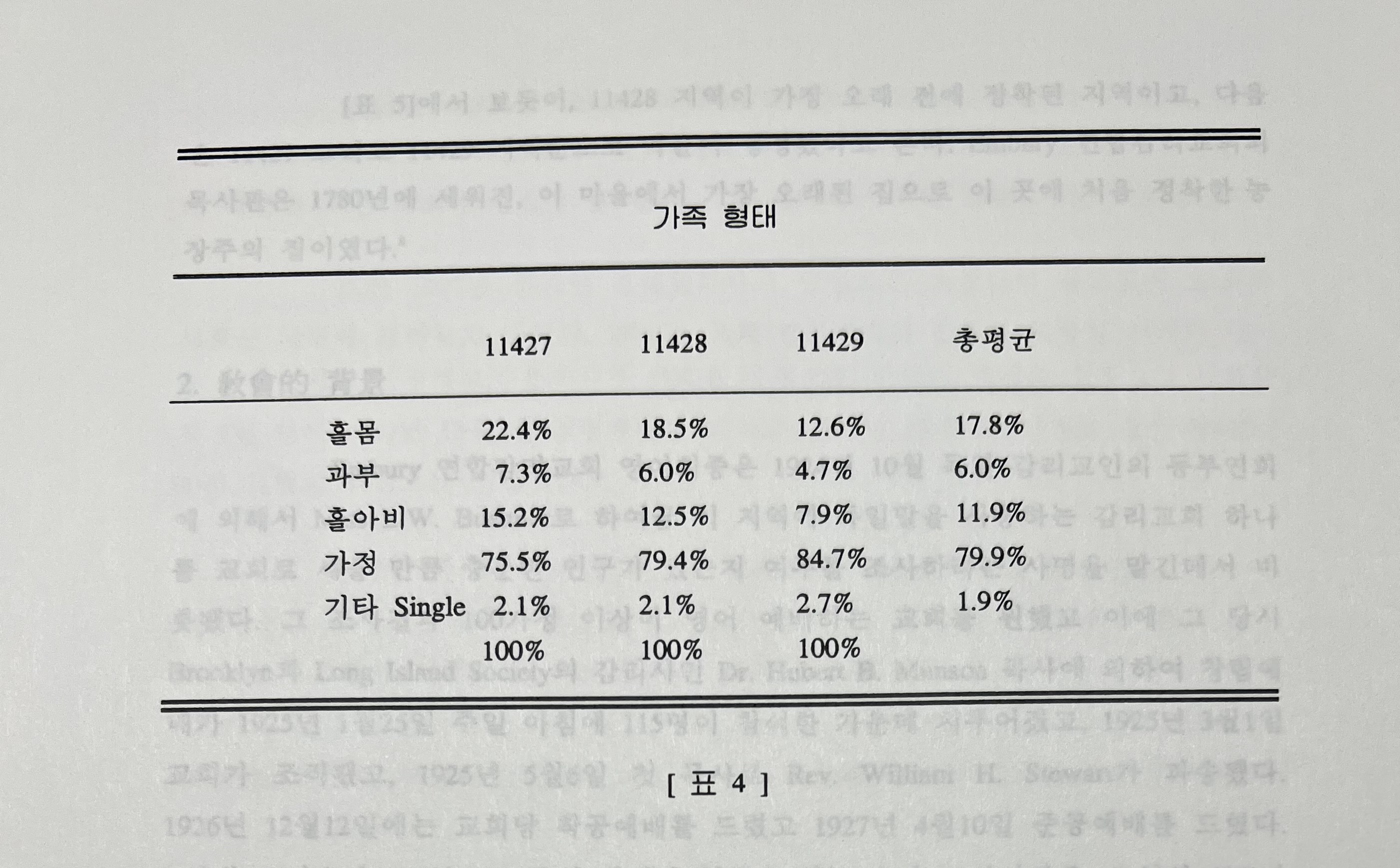

As shown in [Table 4], the White-populated areas of 11427 and 11428 have more elderly people living alone compared to the predominantly Black-populated area of 11429.

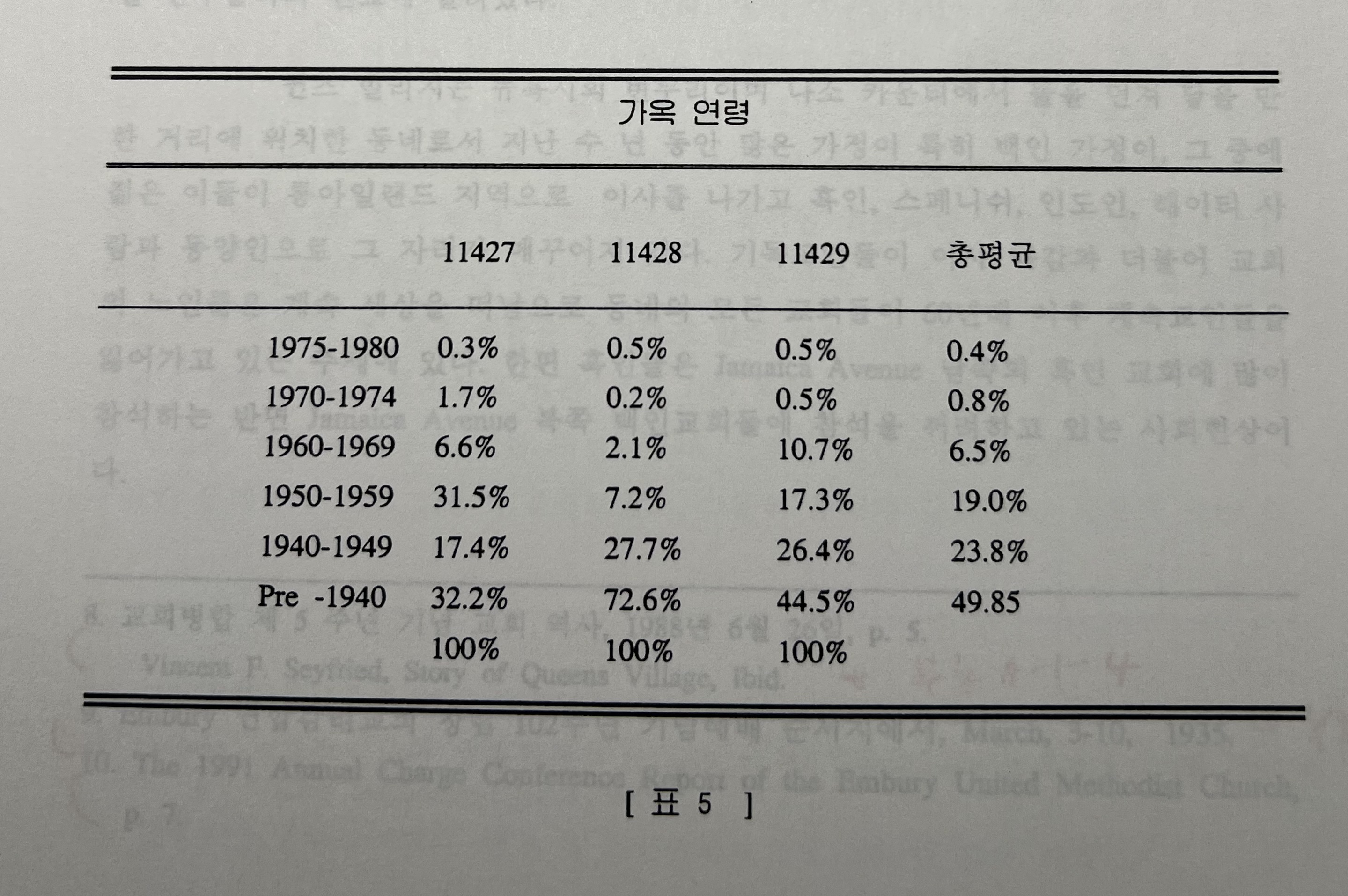

As shown in [Table 5], the 11428 area is considered the earliest settled part of the neighborhood, followed by 11427 and then 11429. The parsonage of Embury United Methodist Church, built in 1780, is the oldest house in the area and was originally the home of the first settler and farm owner in the village.(8)

2. Ecclesial Background

The English congregation of Embury United Methodist Church traces its origins to October 1924, when the Eastern Conference of German Methodists commissioned Miss L. W. Buettner to investigate whether there was a sufficient population in the area to establish a German-speaking Methodist church. The survey revealed that over 100 families desired a church offering worship in English. As a result, a founding worship service was held on Sunday morning, January 25, 1925, with 115 people in attendance, under the leadership of Rev. Dr. Hubert B. Munson, then the District Superintendent of the Brooklyn and Long Island Society. The church was officially organized on March 1, 1925, and Rev. William H. Stewart was appointed as its first pastor on May 6, 1925. Groundbreaking for the church building was held on December 12, 1926, and the dedication service was held on April 10, 1927.(9)

As of now, the church has 256 registered members, with an average of 99 attendees participating in worship and giving offerings on Sundays.(10) About 60% of the congregation are retired elderly people, and 75% are white. The church’s administrative board, which makes decisions about church activities, is composed of 90% white members. Therefore, their values tend to be rooted in past customs, nostalgic memories, and social fellowship with longtime friends.

Queens Village is on the outskirts of New York City, near enough to Nassau County that it could be reached with a stone’s throw. Over the past several years, many families—particularly young white families—have moved to the Long Island area, and in their place came African Americans, Hispanics, Indians, Haitians, and Asians. As Christian families moved away and older church members continued to pass away, churches in the area, including Embury, have steadily lost members since the 1960s. Sociologically, many African Americans attend churches south of Jamaica Avenue and tend to avoid the predominantly white churches north of it.

On June 26, 1983, Embury Methodist Episcopal Church merged with the neighboring Calvary United Evangelical Church.(11) Rev. Thomas Fisher was appointed to the new church and, with a ministry focus on African Americans, the congregation began to see an increase in younger Black families.

In 1987, Rev. Taeheon Yoon, a Korean pastor, was appointed to lead the church, marking a new phase. In 1989, the church board unanimously decided to start a Korean-language ministry.(12) Rev. Yoon began holding Korean-language services at 1 PM with his family, and within a year, the Korean congregation held its founding worship service on December 9, 1990. By the first anniversary in December 1991, the Korean ministry had grown to 31 members with an annual budget of approximately $40,000.(13)

A notable characteristic of the Korean congregation is that 13 members have been involved in intercultural marriages. Of them, five are currently in stable intercultural marriages, two are in the process of divorce, two are divorced and living alone, one has remarried a Korean man after divorce, and one is cohabiting with a Korean man after divorce. They range in age from their 30s to mid-50s and come from various areas such as Astoria, Woodside, Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, and Flushing—not necessarily because of proximity, but due to the human relationships and the unique nature of the church.

Overview of the Issues

To prepare for this study, the author worked with a research team of seven members from the church, and they identified the following facts. The adult Korean congregants can be classified into the following nine types:

- Recently immigrated Korean couples

- Korean couples who have lived in the U.S. for over ten years

- Women living alone after divorcing Korean husbands

- Women in the process of divorcing Korean husbands

- Couples in separation

- Women divorced from African American or Hispanic husbands

- Women in the process of divorcing African American or Hispanic husbands

- Women currently in their first intercultural marriage with African American, Hispanic, or white husbands

- Women in their second intercultural marriage with African American, Hispanic, or white husbands

- Women divorced from such husbands and now engaged or remarrying Korean men

It was discovered that more than half of the Korean congregation struggles with serious family issues, and the severity varies. Often these issues are not visible on the surface—not because they’ve been resolved, but because they have become more deeply internalized. These hidden problems are not exclusive to Embury’s Korean congregation but are widespread among Korean immigrant communities, especially those involving intercultural marriages.

Many adults are receiving psychological counseling or therapy. Korean women with intercultural marriage experience are often seen at the Embury Homeless Shelter, and some end up in state mental hospitals or even prison. T. Richard Snyder refers to such individuals as “the used, the marginalized, the unstable, the despised, the discarded.”(14)

Among the Korean-speaking congregation at Embury, 41% are women with intercultural marriage experience, and 8 out of 13 have been divorced. Due to the psychological, economic, social, moral, and spiritual consequences of divorce, these women often suffer from low self-esteem and severe depression or mental illness, leading to daily lives of poverty and alienation filled with anxiety and struggle.

Root of the Problem: Alienation from Wholeness of Life (Shalom)

The root of this alienation is partially the neglect of established immigrant churches. These churches are often preoccupied with numerical growth, traditional charismatic spirituality, and educational policies focused on church school growth. Several issues emerge here:

- Alienation within Christian families

- Alienation of Christians from society

Following Christ requires a faith that can present the unchanging Christ to new times, places, and cultures—even within the same congregation as society evolves. Alienation occurs when individuals cannot adapt to new cultures. Therefore, even within the same church, there must be continual regeneration for a new era. This requires transformation and sensitive, ongoing responses from the church.

The more critical problem is that no current research, strategy, or practical implementation exists within the church to guide those with “broken wings” or “marginal value” toward the wholeness of life—toward shalom.

This study identifies that the issues at Embury are rooted in alienation from this wholeness and is presented as a humble attempt to respond to the need for transformation through urgent Christian prayer.

Theological Response: Three Areas of Ministry Toward Ecclesiogenesis

- Healing Ministry for Personal Transformation

- Practices for personal transformation toward recovery, aimed at discovering individual identity (Exodus generation).

- Communal Ministry for Church Transformation

- Practices for building a community of equality through collective humanization (Cruciform generation).

- Preventive Ministry for Social Transformation

- Practices by small communities to transform social structures into communities (Peace generation).

Problem Analysis

1) The Human Condition in Immigration

This study addresses the suffering of immigrants who face racial and gender-based discrimination and identity crises. After five years or more in the “land of opportunity and freedom,” many immigrants begin to ask, “Who am I?” They wrestle with:

- Economic survival

- Generational conflicts due to cultural and linguistic differences with their children

- Personal struggles in understanding American culture

- Shame and frustration from not being able to utilize their professional skills or credentials

These struggles cause a loss of self-realization and dissatisfaction in key areas of life:

- Physical needs

- Safety needs

- Social needs

- Self-esteem needs

Immigrants experience invisible pressures and tensions from many directions.

God sees those who suffer—immigrants who have lost freedom in a land of freedom. God desires their liberation. America is a land of pioneers, competition, and enterprise. While it promises crowns to those who demonstrate ability, free competition can also lead others into poverty, hunger, or even death. This creates moral stains in society.

Behind these issues lies the power of systems that dominate individuals. The paradox of religious and social abundance is continually controlled by the demon of conflict. Human relationships are dehumanized, unrecoverable by respect, religion, or social means. Immigrants need help.

Churches must humanize invisible systemic powers while securing the well-being and stability of suffering individuals. Depression results when immigrants lose their dignity. They need motivation to fulfill their hopes.

Therefore, the church must engage in:

- Healing ministry for consciousness-raising: Helping individuals rediscover their identity

- Transformational ministry for humanization: Empathy training for group equality

- Preventive ministry for generative community: Becoming leaven through voluntary suffering to transform society

2) Immigration Process

The history of Korean immigration, particularly the pioneer wave (1882–1905), is generally recognized as beginning with the Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1882, which established diplomatic relations between Korea and the United States. This treaty allowed Koreans the opportunity and freedom to visit and reside in the U.S. While diplomats and students came over soon after, formal immigration is considered to have begun between 1903 and 1905, when 7,226 Koreans traveled on 65 ships to work on sugar plantations in Hawaii. Over 80% were adult men, mostly farmers, laborers, soldiers, church workers, and students. A significant portion—about 40%—were Christians, and most immigrants participated in church life in Hawaii. This initial immigration ended when, in 1905, the Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued an order to ports including Incheon to prohibit Koreans from emigrating.

From 1906 to 1949, immigration resumed with around 2,000 Koreans entering Hawaii and the U.S. West Coast between 1906 and 1924. Immigrants of this era fell into two groups: political exiles and students, and “picture brides”—women who immigrated after agreeing to marry men they had only seen in photographs. A significant number of those early Hawaiian immigrants later relocated to the mainland U.S. and Mexico. Over 2,000 moved to California to work in rice farming and railroad construction, while another 1,000 moved to Yucatán, Mexico, to work in sugar plantations, with many later relocating to Cuba. Today, notable Korean communities still exist in Mexico and Cuba due to these migrations.

In 1924, a highly restrictive U.S. immigration law passed, greatly limiting immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe and completely halting immigration from Korea and other Asian countries. From 1924 to 1945, fewer than 20 Koreans immigrated to the U.S. annually.

Between 1950 and 1969, immigration gradually increased and accelerated in the 1960s. Two reasons contributed to this: (1) U.S. military, political, and economic involvement in Korea following the division of the peninsula and the Korean War, and (2) the reform of restrictive immigration laws in 1965, which opened up immigration from Asian countries. Initially, only 100 immigrants per year were allowed from Pacific Rim nations, but between 1950 and 1969, 32,957 Koreans immigrated to the U.S., and 75,241 entered as students, government delegates, or temporary visitors. Many of these visitors overstayed or obtained permanent residency.

Korean immigrants during the 1950s and 1960s can be categorized into four main groups:

- Women married to U.S. servicemen stationed in Korea. Since 1950, over 40,000 Korean women immigrated as spouses of U.S. citizens, most of whom were soldiers.

- Orphans adopted by American citizens. A New York Times article (March 1, 1977) noted that over 1,300 Korean orphans had been adopted between 1955 and that date; today, the number is much higher.

- Students, trainees, employees of Korean branches, correspondents, and temporary visitors who later gained permanent residency. According to Korea’s Ministry of Education, over 10,000 students studied in the U.S. between 1953 and 1973, most of whom did not return to Korea.

- Professionals such as nurses, doctors, and pharmacists, who immigrated after the 1965 law revision along with their families.

Unlike Korea, where the gender ratio is balanced, Korean-American communities have a female majority—a unique characteristic. In 1970, the male-to-female ratio among Korean immigrants was 33:67. By 1984, this had balanced somewhat to 42:58. This female predominance is attributed to three factors:

- Many U.S. soldiers stationed in Korea married Korean women and brought them to the U.S.

- A higher proportion of adopted Korean orphans were girls.

- A large number of Korean nurses immigrated to the U.S.

The gender ratio became more balanced in the 1980s due to the decline in nurse immigration.

Professor Byung-Kap Min identifies two primary reasons why gender equality is difficult to achieve within Korean immigrant communities:

- Many Korean families run small businesses, where women often work alongside their husbands. However, this shared labor does not translate into independent economic power unless the woman is independently employed and paid under her own name.

- Since most work in Korean-owned environments, Korean language and culture are preserved longer, reinforcing traditional male-dominant customs. Korean language and customs inherently reflect gender distinctions, making gender equality difficult without broader cultural assimilation.

3) Understanding Bicultural Families

Bicultural families typically refer to international and interracial marriages—households formed between partners of different nationalities or cultural backgrounds. As a multicultural society built through immigration, the U.S. has been the subject of numerous sociological studies on such families. With the rise of Korean immigration, many churches have begun focusing pastoral care on bicultural families.

In particular, the families this study focuses on are those formed by about 130,000 Korean women who married U.S. servicemen stationed in Korea after the Korean War. Many 1.5 or second-generation Korean-Americans are also entering interracial marriages, especially in smaller cities or rural areas with low Korean populations, where interracial marriage rates exceed 50%. Thus, ministry for international and bicultural families must expand and diversify.

4) Historical Background of Bicultural Families

According to Korean Ministry of Health and Immigration data, Korean immigration surged after the 1965 law reform. But even before this, many immigrants were family members or acquaintances invited by Koreans in international marriages. Post-Korean War society suffered from poverty, instability, and urbanization, and women faced unequal access to education, jobs, and fair treatment. For many young women—especially from rural or low-income urban areas—international marriage offered a rare chance to immigrate to the “dreamland” of America.

Korean women who married U.S. servicemen endured deep loneliness. Leaving their homeland to marry foreigners often meant permanent separation from their families. In the 1950s, ’60s, and early ’70s, cultural isolation and poor adaptation led to serious emotional distress, unlike today when Korean churches, restaurants, airlines, and media provide some cultural connection.

5) Understanding Bicultural Families

Military families formed through international marriage face frequent relocations and cultural misunderstandings, including conflicts over food and family norms. These challenges often lead to divorce or separation. Difficulties also arise in transmitting Korean culture to children and maintaining relationships with American in-laws. Women face language barriers, adjustment issues, feelings of alienation, stress, abuse, and social neglect. Emotional distress can manifest as instability in marriages and church communities. Yet many women endure and build successful bicultural families through faith and pride in their heritage.

These women exhibit patience, loyalty, cooperation, adaptability, strong faith, patriotism, and familial devotion. Many became exemplary figures in the immigrant community through perseverance and moral strength.

They contributed significantly to Korean society, both financially and socially, and played a cornerstone role in developing immigrant churches. Many quietly supported family reunification and welfare, though their efforts remain largely unrecognized. They acted as ambassadors, sisters to students, relatives to adoptees, and advocates for minority rights in the U.S. Despite being isolated and unsupported in a foreign land, their contributions deserve gratitude and recognition.

(1) Three Stages of Alienation Experienced by Most Internationally Married Women in the U.S.

The first stage of alienation begins when internationally married women arrive in the U.S. with high hopes and dreams, only to experience disappointment and disillusionment. In many cases, these women come from difficult family backgrounds or adverse life circumstances in Korea. Marrying American soldiers, they crossed the Pacific dreaming of a Cinderella-like happiness in the U.S. However, upon arriving at their “homes,” their dreams often collapse. Their husbands’ low income, communication difficulties with in-laws due to language barriers, cultural differences, and the husbands’ indifference—stemming from the end of their own isolation in a foreign country—all contribute to marital tension, especially when the wives face language and cultural shocks. One Korean woman married through international marriage reported that 85–90% of such couples divorce within a few months of marriage.

Some husbands provide no financial support at all, leaving women—who lack language skills and understanding of societal norms—completely abandoned. They are suddenly thrust into a state of anxiety and fear of the future, feeling completely rejected by society. In extreme cases, they lack shelter, income, access to their children, stable employment, and even worry about getting three meals a day. They become what society would call “third-class citizens,” suffering severe psychological trauma.

The second stage of alienation manifests as follows: women who leave their homes often move to cities where their friends live. With no job skills or preparation for the workforce, about two-thirds end up working in massage parlors, where prostitution is frequently practiced alongside massage services. In an attempt to forget their past and escape from extreme loneliness and fear of the future, many turn to alcohol and drugs.

The third stage of alienation is the final phase of life for some of these women. Due to mental instability, schizophrenia, or chronic illness, they lose their jobs and often end up moving from one homeless shelter to another, or are institutionalized in mental hospitals. When they are deemed a threat to themselves or others, local clinics or hospitals in each borough diagnose them and transfer them to state psychiatric hospitals (e.g., in Queens Village). Since hospitals do not release patient information, it is difficult to determine the exact number of Korean patients. Some women are imprisoned for drug use or trafficking, awaiting the end of their sentence in city or state correctional facilities. Even when released on probation, they lack shelters or advocates to support them, leading many to return to massage parlors or drug-related activities. This is clearly a form of social evil created by the system. Yet, there are no shelters specifically for Korean women to address these issues. This is the tragic reality of being alienated from a life of wholeness—SHALOM—in a foreign land.

(2) Three Forms of Alienation Among Korean Women in International Marriages in the U.S.

The dehumanizing issues faced by internationally married Korean women can be categorized into three forms of alienation. A wholeness of life comes from personal integrity and responsibility, mutual respect in human relationships, and commitment to social justice. However, society fails to provide the foundation for such a life for internationally married families. Thus, the following categorization of alienation helps us seek directions toward solutions.

I. Alienation from Personal Integrity and Responsibility (Issue of Consciousness)

Our church’s research group has found that the intense loneliness (the first stage of alienation) experienced by international marriage women leads easily to low self-esteem. While they are aware that their problems are serious, they often do not understand the root causes. These women, underestimating their abilities, fail to achieve inner peace even as homemakers. Without understanding the question, “Who am I?,” peace and a whole life are not possible. This paper views the discovery of personal identity (Who I Am) as the foundational starting point in the transformation process toward biblical ecclesiogenesis.

II. Alienation from Mutual Human Respect (Issue of Humanization)

Our church study group discovered that international marriage couples often struggle to form genuine relationships due to differences in language, culture, food, and thought between husbands and Korean wives. Deep-seated jealousy disrupts even church life and causes frequent conflict with close friends. These issues often occur against the will of the women. Although they try to overcome their alienation, their lack of training in patience and resilience means that church life has little positive effect on their relationships.

Consequently, many women hesitate to participate in church events, although they are comfortable sharing feelings and thoughts with each other. Nevertheless, conflict and confrontation frequently arise among them, only to disappear as if nothing happened. They also tend to change churches often rather than settling in one place. These interpersonal issues reflect a lack of experience with personal responsibility and perseverance. Thus, peace cannot be found within family, friendships, or community. These women live in isolation from the Korean community, missing many opportunities to serve or engage. Some even hide the fact that they are in international marriages, avoiding social contact altogether. This is similar to how some Korean churchgoers avoid social service. It is deeply unfortunate, yet undeniable, that the Korean community has historically discriminated against international marriage women, both verbally and behaviorally. Without knowing who we are or understanding others, a whole and peaceful life is not possible.

III. Alienation from Structural Peace (Issue of Dialogical Community)

Most internationally married couples maintain personal relationships within their own circles, often based on the husband’s race. Thus, no strong or effective social organization exists for them. Though some women once formed a social club with about 30 members, it dissolved after three years. When their husbands abandon them, these women have no institutions to turn to for help—and often hide their situations out of shame. There is one shelter run by the Asian Women Center in Manhattan, but it only accepts victims of domestic violence, making it largely inaccessible to many Korean women.

Additionally, we must not overlook the invisible but deeply rooted discrimination within the Korean community against internationally married women. It is rare to find peace or reconciliation grounded in social justice within the immigrant community on behalf of these women. Considering how few Korean parents approve of their children marrying someone of another race, it is clear that the Korean immigrant community needs a strong awakening of communal consciousness to escape structural racism and achieve genuine social justice.

The Embery faith community models a church that forms a faith-based community for women on the margins, much like Jesus ministered to outcast women and focused his mission on ecclesiogenesis. This may seem a small effort, but the theories and methods applied here can be used in any situation of alienation so that the church may continuously be generated as the living body of Christ.

Our church research group has come to a shared understanding of these issues. We agree that these problems must be deeply studied and addressed at their root. The church, as the Body of Christ, is not merely an institution or building—it becomes a healing and transforming community through the recognition of individual identity (self in the image of God), relational identity (dialogue within community), and responsible identity (creative, outward engagement for social transformation). This transformation moves through a continuous process of personal awareness, church humanization, and social creation. Through such a repeated and ongoing practice, the church—together with its structures, buildings, and members—can become a newly generated church, equipped for true mission.

[Notes]

- Vincent F. Seyfried, The Story of Queens Village, New York, The Centennial Association, 1974, p. 11.

- Ibid., pp. 7 & 9. See Appendix [A-1-2]

- Ibid., p. 11

- Ibid., p. 87.

- Queens County Times, September 16–23, 1971, pp. 8–9. See Appendix [A-1-1]

- Queens Village Chamber of Commerce, The Queens Village Guide, 1989, p. 19.

- [Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5] are from MARKET STATISTICS, a division of Bill Communications, Producers of the Survey of Buying Power, 633 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, May 15, 1990.

- The 5th Anniversary of the Church Merger: Church History, June 26, 1988, p. 5.

Vincent F. Seyfried, Story of Queens Village, Ibid., and Appendix [A-1-4] - From the 102nd Anniversary Worship Program of Embury United Methodist Church, March 3–10, 1935, and Appendix [A-1-3]

- The 1991 Annual Charge Conference Report of the Embury United Methodist Church, p. 7.

- The 5th Anniversary of the Church Merger: Church History, Ibid., p. 1.

- Minutes of the Administrative Board of Embury United Methodist Church, September 1989.

- 3rd Congregational Report of Hallelujah United Methodist Church, December 29, 1991. See Appendix [D-1]

- T. Richard Snyder, Once You Were No People (Bloomington, IN: Meyer Stone Books, 1988), p. xiv.

- Min, Byung-Gab, Minority Ethnic Groups in the United States, (New York: Queens College, 1990), p. 158.

- Ibid., p. 159.

- Ibid., pp. 170–171.

- Ibid., pp. 185–186.

- Lee, Boo-Duk, “The Direction of Ministry for Intercultural Families,” United Methodist Family, Vol. 5 No. 2, Fall Issue, pp. 14–15.

- The term Ecclesiogenesis was coined by Father Leonardo Boff in Brazil, South America, in a context of poverty and political dictatorship, to express the idea that traditional church structures could not realize freedom, justice, and love. He combined the words Ecclesia (church) and Genesis (creation) in his book Ecclesiogenesis. In this paper, the author adopts and interprets this term as “Church-Birthing.”

In this paper, Ecclesiogenesis is defined as the spiritual practice and collective process of Christians who strive to transform the deeply rooted causes of alienation in society and in the church. This ongoing process of transformation is referred to as “transforming praxis.” Thus, the author regards church not as a building or institution, but as a dynamic event and process.