“THE TRANSFORMING PRAXIS TOWARD ECCLESIOGENESIS, Church Rebirth” (Chapter One)

What Is the Transforming Praxis Toward Ecclesiogenesis?

The title of this dissertation, The Transforming Praxis Toward Ecclesiogenesis, originates from two key sources: First, Once You Were No People, written by Dr. T. Richard Snyder, who oversees the Doctor of Ministry program at New York Theological Seminary. In this work, Dr. Snyder explores the role of the church in social transformation. Second, Ecclesiogenesis, authored by Father Leonardo Boff, which reflects on his missionary experiences among the poor in Brazil and critiques the current structure of institutionalized churches. Boff calls for a reinvention of the church as a foundational community movement built upon the tradition of the existing church, oriented toward the coming Kingdom of God.

As noted in the introduction, Korean women in intercultural marriages often undergo a process of dehumanization marked by three primary forms of alienation:

- Alienation from Self-Identity,

- Alienation from the Relational Self, and

- Alienation from the Responsible Self.

These three forms of alienation are generally assumed to begin when women arrive in the United States after marrying, but this research reveals that such experiences of alienation often begin much earlier—during childhood and adolescence in their families of origin—and are perpetuated throughout their lives. In fact, they often repeat these three stages of disconnection, and paradoxically, even fear and resist a more humanized life beyond these patterns of alienation.

These women experience:

- Alienation from personal integrity and responsibility—a loss of humanity that manifests in cultural shock and maladjustment in unfamiliar environments and among unfamiliar people. This disrupts not only their marital and domestic lives but also extends into their social participation, leading to deep psychological oppression.

- Alienation from mutual human respect—when intercultural couples fail to withstand such pressures, the relationship collapses. Divorce often follows, and post-divorce, these women face extreme poverty due to a lack of experience and knowledge about American society.

- Alienation from a socially responsible self—this alienation does not arise solely from their own choices. Rather, it can be traced back to unresolved trauma and dysfunction within their families of origin. Many of these women were already victims of alienation as children. Later, after immigrating, they find no system of support or understanding from the Korean American community. In fact, despite sharing a common ethnic identity, they are often treated as “third-class citizens,” with no advocacy group or institutional structure to defend their rights or welfare.

At this point, many of these women fall into helplessness and confusion—about themselves and their place in society. They eventually descend into the most dehumanized forms of existence: working in bars or massage parlors, living on the streets, falling into drug abuse or trafficking, being institutionalized in psychiatric hospitals, or imprisoned. Some even become homeless. This is the tragic reality faced by many Korean women in intercultural marriages as a result of systemic and personal alienation.

This dissertation seeks to confront and respond to that alienation through a theological and ecclesial framework. The Transforming Praxis Toward Ecclesiogenesis envisions a new, liberating form of church that actively affirms human dignity, restores identity, and rebuilds community—particularly for those on the margins.

1. What is Alienation?

What does “alienation” mean in the context of Transforming Praxis Toward Ecclesiogenesis? According to the New Korean Dictionary, alienation (疎外) is used as both a noun and a transitive verb. Its meaning is “to create distance between and repel” (estrangement). Synonyms include so-cheok (疏斥) and so-won (疎遠). So-won, in particular, is defined as “a state in which intimacy weakens, and the relationship becomes awkward and distant.” A synonym for this is so-jeok (疏狄).

According to Webster’s New Universal Unabridged Dictionary, alienation has the following meanings:

- The legal transfer of ownership or property to another party.

- The state of being alienated.

- Emotional estrangement or loss of affection, growing apart, withdrawal, or separation.

- Mental derangement, ecstasy, frenzy, disturbance, madness, or insanity.

The New Encyclopaedia Britannica defines alienation in the context of social sciences as a feeling of being distant or disconnected—from one’s environment, work, or even oneself. It presents six common meanings of alienation:

- Powerlessness: Believing that one’s fate is not in one’s control but determined by external forces such as institutions, fate, luck, or structural systems.

- Meaninglessness: A lack of understanding or purpose in global events or interpersonal relationships, leading to a sense that life lacks coherent direction.

- Normlessness (Anomie): A lack of commitment to shared societal norms or prescriptions for human behavior, resulting in widespread mistrust, deviation from common sense, or chaotic individual competition.

- Cultural Estrangement: Being removed from the prevailing cultural values of society. This is often observed among intellectuals or students who rebel against traditional institutions.

- Social Isolation: The feeling of being excluded or lonely in social relationships. This often applies to minority groups.

- Self-Estrangement: Perhaps the most difficult and central concept—where a person feels fundamentally disconnected from themselves and cannot relate meaningfully to their own identity.

Though the concept of alienation began to be formally recognized in Western social sciences after 1935, it was implicitly or explicitly present in the writings of 19th- and 20th-century classical sociologists such as Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, Ferdinand Tönnies, Max Weber, and Georg Simmel.

Karl Marx famously used the term in reference to alienated labor under capitalism, defining it as:

- Labor that is forced rather than voluntary or creative.

- Workers have little control over the production process.

- The products of labor are appropriated and used by others, against the worker’s will.

- Workers themselves become commodities in the labor market.

Marx’s concept of alienation is rooted in the idea that humans are unable to realize their “species-being” through their work—this is the essence of what he considers humanity’s fall into an unknowable condition.

This Marxist tradition represents only one stream of alienation theory. A second stream, less optimistic about overcoming alienation, is represented by mass society theory. As they observed the disruptions caused by industrialization in the 19th and early 20th centuries, thinkers like Durkheim, Tönnies, Weber, and Simmel lamented the loss of community and the disintegration of traditional society. Modern individuals began to experience unprecedented isolation, anonymity, and impersonal urban life, and felt uprooted from old values.

Durkheim’s concept of anomie is perhaps the clearest definition of this: derived from the Greek word anomia (lawlessness), it refers to social situations characterized by normlessness, fragmentation, and pervasive individualism. Weber and Simmel developed this further—Weber emphasized increasing rationalization and formalization within social structures that lead to dehumanized bureaucracy, while Simmel highlighted the tension between subjective individual life and the growing impersonality of objective modern life.

The earlier classification of alienation into the six categories—(1) powerlessness, (2) meaninglessness, (3) normlessness, (4) cultural estrangement, (5) social isolation, and (6) self-estrangement—was meant as a general framework toward developing a more advanced conceptualization. For example, in the case of self-estrangement, a person can become disconnected through various different paths.

Later, definitions and hypotheses diverged significantly. Two contrasting perspectives are:

- Normative: Scholars such as Herbert Marcuse and Erich Fromm in the U.S., and Georges Friedmann and Henri Lefebvre in France, aligned with the Marxist tradition. They treated alienation as a normative concept to criticize fixed social conditions based on principles of humanity—akin to natural law or moral standards.

- Objective: Marxists argue that alienation is an objective condition, independent of individual consciousness. For instance, a “happy robot” at work is still alienated, regardless of how the person feels about their job.

On the other hand, most American empiricists and authors see alienation as a social-psychological fact, an experience of powerlessness or a sense of estrangement. This assumption frequently appears in analyses of deviant behavior, such as those studied by theorists like Robert K. Merton and Talcott Parsons.

T. Richard Snyder claims that alienated people lack names and are not treated as true humans, thus cannot be considered truly human. He categorized six types of alienation:

- Alienation from neighbors: Including racial divisions (Black and White, Anglo and Hispanic), generational divides (young and old), economic gaps (rich and poor), and religious or regional divisions (Protestant and Catholic, natives and newcomers). These walls of division can lead to extreme forms such as apartheid in South Africa, the Holocaust under Nazi rule, or modern economic hostilities. In Korea, women in military camptowns suffer from severe alienation, treated as a special group only to serve American soldiers. Similarly, divorced Korean women in intercultural families in the U.S. often work in underground massage parlors to survive—an example of alienation within the Korean immigrant community, and of racial and gender discrimination.

- Alienation from work: For modern people, work has become a necessary evil. Unlike God, who planned and delighted in His creation, most people don’t do the work they desire, nor are they satisfied with or able to see its results. Marx argued that this alienation results from workers being reduced to mere tools of labor, as ownership of production is concentrated in the hands of a few. According to Marx, all other forms of alienation stem from this fundamental economic alienation. In immigrant communities, many people do not pursue their desired jobs and are dissatisfied with the outcomes. Women from intercultural families who experience failure often prioritize labor as a survival tool over maintaining community ties. Of course, we know well that Marx’s focus on the economic aspect of human life was limited. He did not deal with many other aspects of human existence. While poverty and unemployment can lead to crime, the more critical issue is that when people lack the ability to manage their lives, it results in anger and destructive behavior—something Marx and his followers often overlooked. Regardless of whether we adopt Marxist analysis, most of us cannot deny that work is often experienced as a form of alienation.

- Alienation from the environment: Urban dwellers directly experience alienation from nature. Modern civilization, in its effort to dominate the natural world, is now threatened by disease, fear, and death. Alienation has intensified more than at any other time in history. Treating nature as a mere resource destroys our ability to grasp its integrity and balance. We alienate ourselves from the environment, of which we are a part.

- Alienation from institutions: In advanced countries like the U.S., we feel that national health systems are even worse than those in Cuba. Educational systems are failing—New York City’s policy has failed, and illiteracy has become a national issue. Institutions originally created to serve us now alienate us from our own lives.

- Alienation from oneself: Like seeing ourselves through a broken mirror, we cannot see our true selves clearly. Many people cannot live as their true selves or become the person they want to be.

- Alienation from God: Human alienation begins and ends in the relationships that define human existence. From the biblical perspective, alienation occurs when humans seek self-righteousness and become estranged from God. The root of human alienation is found in humanity’s separation from God—the Ultimate Cause and Creator of all things. When people attempt to live apart from God, they become estranged not only from the Creator but also from themselves, others, and the world.

- This type of alienation is most fundamentally a spiritual estrangement, resulting in a breakdown of relationship between the divine and the human. Theologically speaking, sin is the source of this estrangement. In Genesis, Adam and Eve’s disobedience is portrayed as the starting point of this alienation. Once separated from God, they also became alienated from each other, from nature, and from their own sense of identity. This is the comprehensive nature of alienation that the Bible addresses.

- The redemptive narrative of Scripture consistently seeks to reconcile this alienation. Through the covenant, the Law, the Prophets, and ultimately through the person of Jesus Christ, God reaches out to restore the broken relationship. In Christ, the alienated human being is invited back into communion with God. This restoration is not merely spiritual or abstract; it includes a transformation of how one relates to self, others, society, and the environment. Salvation, in this sense, is the overcoming of alienation on all levels.

- In conclusion, alienation is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon. It manifests in personal, social, economic, cultural, environmental, institutional, and spiritual dimensions. Whether understood through Marxist critique, sociological analysis, or theological reflection, alienation reflects the deep fractures in human existence. It is a central issue that must be addressed if one seeks genuine transformation and community formation—especially within the context of ecclesiogenesis, or the birth of the church.

- The praxis of ecclesiogenesis thus involves a transformative response to alienation. It seeks to create inclusive, healing, and participatory communities where alienation is actively dismantled and authentic belonging is fostered. In such communities, individuals are no longer objects or commodities, but are recognized and embraced as whole persons made in the image of God.

2. What Is Transforming Praxis?

The terms “transformation” and “praxis” can be used to describe the movement from closure to openness—a liberation toward shared life and mutual living. Though similar in meaning, “transforming praxis” emphasizes the process of practicing transformation itself.

Richard J. Bernstein explains “praxis” as follows:

“Praxis is a Greek term that means ‘practice.’ Sometimes it is translated as ‘action’ or ‘doing.’ But praxis does not refer to general activity; it refers to specific kinds of action. More precisely, it is action aimed at social transformation—activity that directly influences social existence.” (36)

Thus, transforming praxis is an intentional effort to convert closed individuals and societies into open ones. This process may be theorized through three dimensions:

- Character (성격) – referring to virtues worthy of praise and vices deserving blame.

- Action (행동) – indicating ethical responsibility and obligation.

- Value (가치) – indicating the ultimate purpose or goal of human life, regardless of whether the justification is good or flawed.

Paul F. Knitter notes that praxis is both the method and core of liberation theology and Christology. Praxis is not merely an application of theory or a means to an end. Rather, it is “the foundation that generates theory and corrects itself.” (38)

We do not first know the truth and then act on it; rather, truth becomes known and validated through action.

Liberation theology, in particular, prioritizes orthopraxis (right action) over orthodoxy (right belief), challenging doctrinal authority in favor of lived transformation. Gustavo Gutiérrez asserts this poignantly:

“The subject of liberation theology is not theology—it is liberation.” (40)

This means that doctrinal and canonical forms of the past, while still normative in some cases, are not absolute standards. The “truth” of doctrine or tradition must always be judged by the ultimate mediator of truth—the transformative response of praxis. There is no such thing as “right knowledge” (orthodoxy) without “right action” (orthopraxis).

In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire emphasizes the inseparability of action and reflection. In the struggle for liberation, the two cannot be separated. He argues that authentic speech—language that transforms—only exists when thought and action are united. When action is detached from reflection, both stand isolated; reflection cannot be evaluated, and action becomes misguided.

In any transforming praxis against racism, sexism, ageism, and classism, three components must be integrated:

- Action

- Reflection

- Critical Reflection (in its later phase)

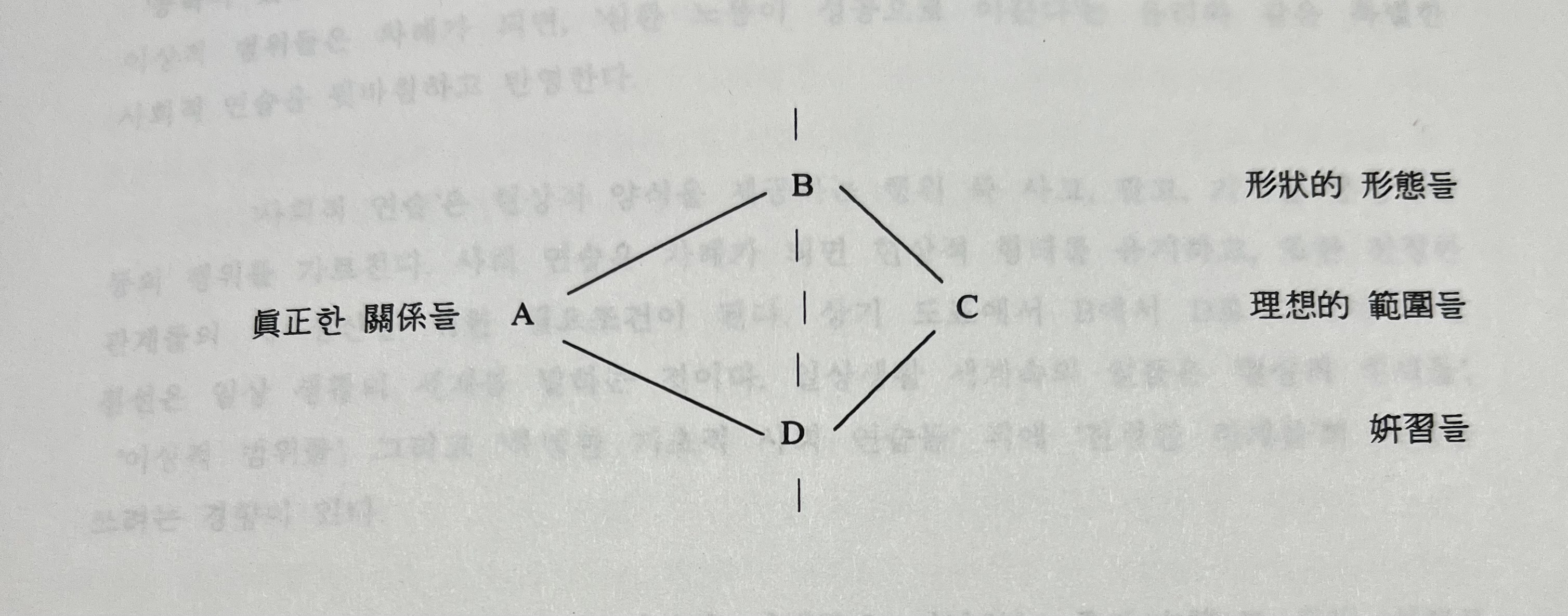

As shown in [Figure 1], the character of transforming praxis is relational and tripartite, resembling a three-legged framework.

[Figure 1]

This framework represents the interconnectedness and interdependence inherent in human life. As Bernard M. Loomer states in his unpublished essay, The Web of Life,

“This web is the ever-present, inescapable structure embedded within life itself.” (41)

Human morality and personal identity are shaped by—and continue to emerge from—the dynamic network of relationships in which they are embedded. Thus, Allan Aubrey Boesak insightfully notes:

“A person becomes truly human only in solidarity with others and in service to others.” (42)

Transforming praxis aims to turn closed individuals and societies into open ones through three theoretical hypotheses:

- Character

- Action

- Value

Character refers to virtues or moral dispositions, action to ethical responsibility, and value to the human purpose behind all endeavors.

The Four Hermeneutical Steps of Transforming Praxis for Ecclesiogenesis:

- Identity Recognition (Interpretive)

- Action (Relational Complementarity and Mutual Dependence)

- Reflection (Social Action)

- Prophetic, Critical, and Self-Reflective Feedback

In this framework, the first step of transforming praxis in ecclesiogenesis is healing—helping individuals, families, and communities recognize and form their identity through interpretive methods.

The second step involves praxis itself, as a form of action and knowing that emerges through identity and self-reflection. This is a mutually complementary and interdependent process.

The third step is social action, involving concrete engagement in community transformation and structural change.

Finally, the fourth step—prophetic, critical, and self-reflective reflection—feeds back into the first stage, continuing the cycle of identity transformation within individuals and communities.

1) Healing Through the Hermeneutical Method

Critical interpretation leads to healing. As a witness to the living presence of God, the Korean intercultural house church serves not only as a space for worship and fellowship but also plays the role of a critical interpreter.

The hermeneutical role includes:

- Understanding the historical and cultural background of intercultural families to encourage self-respect, faith, and action.

- Engaging the limiting and oppressive events in these families’ lives through responsible faith.

- Reinterpreting Scripture to nurture relational and healing patterns that reflect God’s active presence with the oppressed of our time.

The intercultural house church is challenged to expose and transform social structures of exploitation, often hidden in capitalist systems. It must also reinterpret the traditional Korean culture that historically enslaved women, empowering victims to make independent choices and cultivating new relational patterns.

Helping the oppressed merge into mainstream society is not enough. The intercultural family church is historically challenged to do more—transforming unjust social structures and redefining labor and relational systems toward a more humanized order. This process of identity recognition is the healing step through hermeneutics.

The path to an open society hinges on conscientization. Awareness of one’s identity and others as true humans requires consciousness transformation.

If human beings are responsible for fulfilling personal and social histories, they need to go through a self-awareness process that helps them learn to act toward realizing the world. This process—aimed at developing new consciousness and capabilities—is called conscientization.

This concept, popularized by Latin American theologians such as Helder Camara, Paulo Freire, and Gustavo Gutiérrez, is a key feature of Latin American theology.

Freire defines conscientization as:

“The continuous process of perceiving social, economic, and political contradictions and taking action against the oppressive elements of reality.” (43)

Thus, conscientization is not a psychological tool for feeling better—it is a communal effort toward personal and societal transformation.

2) Relational Complementarity and Mutual Dependence

The Korean intercultural house church, by its very nature, is compelled to be a relational church. It must heal, support, and care for marginalized, mentally distressed, and socially abandoned people—offering spiritual nourishment.

Intercultural families face double oppression through racial and gender discrimination, leading to profound dehumanization. Healing must begin not only in these families but also in the consciousness and structure of the entire society.

Therefore, the church must adopt new spiritual practices—a liberative praxis of mutuality and equality, shaped through identity and self-reflection in specific dehumanizing contexts.

Korean women in intercultural families often internalize inferiority and self-harm, consequences of racism and sexism. The liberation of both Korean society and broader society depends on recognizing these issues and creating pathways toward egalitarian transformation—this is ultimate healing.

This second stage of therapy through relational collaboration and mutual dependence can also be understood in contrast to the six “alienation traps” mentioned by Snyder. These are the results of internalized perspectives shaped within closed societies.

To understand what an open society entails, we turn to Henri Bergson, who first systematically theorized the contrast between “open” and “closed” societies in his later work The Two Sources of Morality and Religion (44). According to Bergson:

- An open society is founded on open morality and dynamic religion.

- A closed society is grounded in closed morality and static religion.

Karl Popper offers a different perspective in his famous work The Open Society and Its Enemies (45). Rather than mysticism, Popper advocates for a rational, reason-based open society. While he appreciates Bergson’s emphasis on universal love, Popper rejects the idea that mystical intuition alone can bring about an open society. In fact, he warns that irrational mysticism may become a threat to openness.

According to Popper, closed and open societies are distinguished as follows:

- A closed society is biologically organic and collectivist, where the individual cannot exist apart from the tribe or group.

- An open society is abstract and impersonal, characterized by new human relationships formed through free choice rather than inherited structures. Communication is often conducted impersonally—through typed letters or electronic means—and individuals are physically and socially isolated but mentally connected by shared ideals.

The second level of transforming praxis—relational complementarity and mutual dependence—serves as the opposite pole to the six alienation traps mentioned by Snyder. These six alienations are:

- Alienation from self

- Alienation from others

- Alienation from institutions

- Alienation from creation

- Alienation from the present and future

- Alienation from God

These alienations develop as internalized mindsets and worldviews, formed within closed societies. Healing from these conditions requires a move toward openness—a process that emerges through relationships grounded in equality and mutual care.

In open societies, individuals are encouraged to form voluntary relationships rather than conform to inherited or imposed roles. As Karl Popper observes, open societies are abstract and impersonal, relying more on shared ideals and principles than on collective identity or tribal belonging. However, these societies also carry a risk: people may become physically and socially isolated, even as they are mentally and emotionally connected through modern communication.

ltural house church becomes not only a site of healing and belonging, but also a sign and instrument of God’s reign in the world.

1. A closed society is a biologically organic society—a tribal or collectivist society that believes an individual cannot exist without the tribe or group. In contrast, an open society is an abstract society that lacks organic characteristics. All communication is conducted through typed letters or telegrams, and all affairs are managed by isolated individuals traveling in sealed automobiles. It is an impersonal society, but it allows for the emergence of new human relationships chosen freely. This represents a phenomenon where spiritual bonds replace biological or physical ones. For example, members who pay dues to the Red Cross may have never met, yet they form a family in spirit by sharing a desire to help neighbors in need.

2. A closed society views all institutions and norms, including class systems, as sacred and inviolable taboos. It is a society based on monism that lives under the rule of historical fate. In contrast, an open society is a creative society. This creativity is supported by a critical dualism that strictly distinguishes facts from values. In such a society, the responsibility for moral norms cannot be ascribed to nature or God; humans must improve them themselves.

3. A closed society, regardless of the size of its state, seeks to regulate the entirety of civil life—this characterizes a politically totalitarian society. The state becomes an object of idol worship. Aristotle even considered it ideal for the state to care for the virtues of its citizens. Therefore, individuals have no right to determine what is right or wrong. Conversely, an open society is one in which individuals can make their own judgments and independent decisions.

When considering these characteristics as a whole, Popper’s open society is ultimately a society where individual freedom and dignity are secured. It is a society where individuals make their own judgments based on reason and take responsibility for their actions. Such a society can be interpreted as a democratic society that holds freedom, equality, and love as its ideals.

Between the two types of open society—one based on Bergson’s mystical religion and the other on Popper’s rational reason—the latter is considered the more genuinely open society. This is because mysticism can be interpreted as a longing for the lost closed society, or even as a reactionary movement against the rationalism of the open society. Therefore, we can define an open society as follows:

(1) A society that transcends biological bonds, including kinship;

(2) A society that maximally allows for individual freedom and creativity;

(3) A society that considers individual well-being the main purpose of its social structure;

(4) A rational society that rejects dogmatism and allows for critical discourse.

In other words, an open society is one where every individual is valued in themselves; where all resources, including the talents and achievements of the gifted, are used for the happiness of the entire population; a society where freedom and safety coexist with justice and peace; where free individuals share the responsibility of guaranteeing freedom for all; and where critical discussions based on reason are encouraged.

If we define an open society in this way, we can interpret human history as a transition from closed societies to open societies. Natural societies or those just emerging from nature were closed societies. In contrast, societies created by reason were open societies. However, completely closed or completely open societies have never existed in reality. All societies include both elements. Therefore, the distinction between closed and open societies depends on which characteristic is more dominant.

The conflict and struggle between closed and open societies began with human history itself. Human reason aspires to an open society, but human instincts long for the closed society. An open society guarantees human freedom and dignity but demands tension and responsibility in return. A closed society enslaves people to fate, but it guarantees social stability and order. Throughout history, humanity has repeatedly attempted to return to closed societies whenever possible, as it could not withstand the tensions demanded by open societies.

A closed society provides rest and peace of mind instead of tension. However, human society, having embarked on the journey toward an open society, is no longer like an animal society—it cannot return to the innocence and simplicity of the closed society. Once humans begin relying on reason and exercising critical thought, and once they start to feel the responsibility to pursue knowledge and bear personal accountability, they cannot return to a closed society. Those who have eaten the fruit of knowledge have lost Eden. If we shrink from bearing the cross of humanity, reason, and responsibility, we must instead strive to clearly understand the problems facing humanity and strengthen ourselves. This requires considerable effort. It is the minimum price of living as a human. We can return to primitive or animalistic societies. But if we wish to remain human, there is only one path: the path toward the open society.

The path to an open society, which begins with self-reflection comparable to the reflection in a mirror, is ultimately a matter of becoming conscious. The process of identifying one’s true self is also part of this awareness, and true human communication requires recognizing oneself and others as authentic human beings through a process of consciousness-raising and reforming our awareness.

3) Social Action:

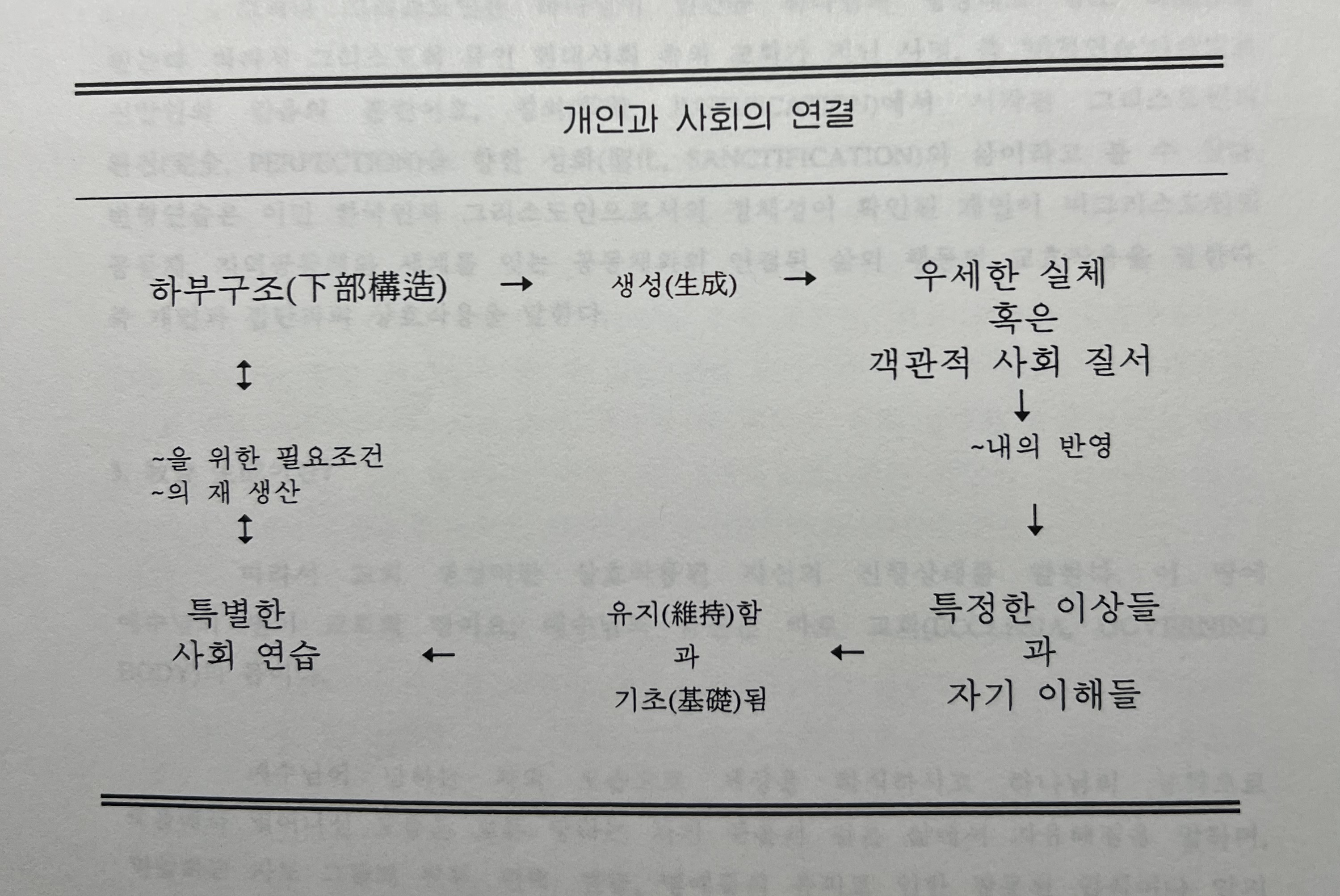

Peter L. Berger, in his book Facing Up to Modernity, briefly summarizes the relationship between the individual and the system (or structure):

“Society collides with the individual, who is a mysterious force. The individual is the unconscious source of the fundamental power that shapes life.” (p.46)

In other words, the reality of the individual exists within relationships. Society does not entirely arise from the conscious and intentional actions of individuals but emerges relatively autonomously from interactions between people. Thus, society is open to transformative human actions. Social liberation and transformation require us to examine the forms of production and reproduction and the organized nature of social relations, and to endure the resulting changes. Society can become an object of serious reflection and knowledge through experience and rational inquiry; it can be reproduced, revised, and even transformed through human action or praxis.

Praxis is the path of knowing and doing, arising from acts of self-awareness (self-consciousness) and self-critique within concrete situations. In this sense, praxis is reflexive action.

The terms “individual” and “system” evoke many images—personal systems, family systems, institutional structures, bureaucratic and social systems. By actively engaging in the interplay among all these systems, individuals become accustomed to them from infancy and shape themselves through them. Over time, these experiences form a coherent identity. The individual, even from infancy, begins to take on subordinate roles in order to enter broader sociocultural and political systems.

The terms “individual” and “system” point toward the interconnectedness between broad socio-cultural and political structures and the individuals within them. Roy Bhaskar offers the following model for thinking about the connection between the individual and society. (p.47)

“Real Relations” refer to the material infrastructure of survival within society. For example, this means the capitalist mode of production. Such a production system necessitates a class society composed of ruling classes, working classes, and the poor. The modern capitalist structure is a highly complex system of productive relations. These foundational structures—real relations—generate the forms of appearance.

“Forms of Appearance” refer to the particular manifestations of social reality as conceptualized in human experience. In capitalism, forms of appearance include the relationship between wages and labor, complex occupational hierarchies, and class structures. These appearances become institutionalized and serve to regulate society.

These forms of appearance present themselves as “dominant realities,” “objective truths,” or simply “how things are.” Unless one critically reflects on the underlying structures that generate these appearances, these surface-level forms are mistaken for truth. However, in their own time, these forms reflect within particular “ideological frameworks.”

“Ideological Frameworks” refer to attempts either to radically transform existing social realities or to legitimize the status quo. Ideologies function to connect subjective beliefs to objective social structures. Examples of ideologies that legitimize the maintenance of capitalist production include ideas like:

- “Those who have, should lead,”

- “The capable succeed,”

- “Poverty is God’s punishment for the lazy.”

These ideological frameworks, when appropriate, support and reflect particular social practices, such as the ethic that “hard work leads to success.”

“Social Practices” refer to actions that provide the form of appearance—such as buying, selling, negotiating prices, etc. Social practices, in turn, sustain the forms of appearance and are a necessary condition for the reproduction of the real relations beneath them.

In the diagram referenced, the dotted line from point B to D indicates the world of everyday life. In everyday life, there is a tendency for forms of appearance, ideological frameworks, and specific basic social practices to mask the real relations beneath.

The key point is that society, while existing as a real entity perceived by conscious subjects and possessing deep resources of authority, is causally connected to the subject through praxis (practice). To clarify this relationship, one could construct a diagram.

Interpretation, healing, sustenance, guidance, and challenge are all social actions that must be integrated. Interpretation must be connected with praxis (practice). Social action must strive for a full understanding and transformation of the entrenched structures of oppression, the social arrangements that maintain them, and the processes involved.

The Church must step beyond its mosaic windows and be present with me where my mother is weeping, where children are hungry, where mothers and fathers are without work, where families suffer from illness but have no insurance. The ministry of social action must cultivate an openness to others’ critical perspectives, just as both the church community and the broader society must continuously develop and expand their practices of care, liberation, and social transformation.

4) Prophetic, Critical, and Self-Reflective Engagement

The intercultural family church plays a prophetic role when it declares judgment through the power of the gospel on exploitative economic and social systems that institutionalize structural inequality and perpetuate covert forms of racism and sexism. This prophetic role must be reflective, asking with utmost seriousness: What are today’s churches and intercultural family churches doing now in the light of Scripture and the cries of the oppressed?

This role only holds meaning when it is consistent with the church’s interpretative work and its ministry of social action.

However, Christians believe that God created humanity in God’s image. Therefore, the mission of the church in today’s society—as the body of Christ—is transforming praxis, which is a spiritual discipline of faith. This transforming praxis can be understood as the sanctifying journey toward perfection that begins with justification.

Transforming praxis refers to the interactive relationship between individual life actions and communities—those of non-Christians, local neighborhoods, and the global society—carried out by individuals whose identities as both Korean immigrants and Christians have been affirmed. In other words, it is the mutual interaction between the individual and the collective.

┌────────────────────────────┐

│ God's Image in Humanity │

└────────────┬───────────────┘

│

┌────────────▼───────────────┐

│ Church's Mission: │

│ Transforming Praxis │

└────────────┬───────────────┘

│

┌────────────────┴────────────────┐

│ │

┌──────────▼──────────┐ ┌───────────▼────────────┐

│ Justification │ │ Sanctification │

│ (Faith Begins) │ (Toward Perfection) │

└──────────┬──────────┘ └───────────┬────────────┘

│ │

└───────────┬────────── ┘

│

┌────────────────▼─────────────────────┐

│ Transforming Praxis (Practice) │

│ – Interpretation + Action │

│ – Healing, Sustaining, Guiding │

│ – Prophetic & Critical Reflection │

└────────────────┬─────────────────────┘

│

┌───────────────────▼────────────────────────┐

│ Mutual Interaction with Communities │

│ – Intercultural Church │

│ – Broader Society │

│ – Local & Global Engagement │

└───────────────────┬────────────────────────┘

│

┌─────────────────▼────────────────┐

│ Social Transformation & Liberation │

└──────────────────────────────────┘

3. What Is Ecclesiogenesis?

Ecclesiogenesis refers to the interactive process of one’s own development toward becoming the church. On this earth, the Spirit of Jesus is the Spirit of the Church, and the body of Jesus is the very body of the Church (Ecclesia, the governing body).

Jesus departed this world as one who suffers and rose from the dead by the power of God. This signifies the liberation of all who suffer from a death-like life. It also points to the liberation of oppressors—from dehumanizing actions, whether committed knowingly or unknowingly, driven by the need to maintain their traditions, power, customs, and honor. This liberation is a resurrection from another kind of death.

The movement that brings about such transformation is ecclesiogenesis. The term was coined by Leonardo Boff, a German-Brazilian Franciscan priest. He advocated for the reinvention of the Church as the body of Christ on earth and as a base for the expansion of God’s kingdom—through Basic Christian Communities (The Base Communities Reinvent the Church). He called for the rebirth of the Church not as a new place or new people, but as a renewal of the existing Church, so that it might become the Church that Christ truly desires. Ecclesiogenesis, then, refers to the re-birthing of the Church on its original foundation, in alignment with pure principles, thus transforming its form and position.

Today, the emphasis on church growth has overshadowed the urgent appeal for church renewal. However, I firmly believe that true church revival is an ongoing process of church renewal. For a church to remain genuinely a church, three transformations must take place:

- The transformation of individual believers,

- The transformation of the church itself, and

- The transcendental transformation of the church’s structure through a renewed relationship with society at large.

Without these, the church becomes nothing more than a social club, a welfare organization, or a general business entity under the guise of the Lord’s Spirit—far removed from the work of God’s kingdom, which is rooted in freedom, peace, equality, love, faith, and hope.

Just as we cannot define the church as a building, ecclesiogenesis refers to the construction of a living church through Basic Christian Communities. In such a foundation, there is no structure of exclusion. It is characterized by direct relationships, mutual interactions, deep communion (eucharistic relationships), cooperation, shared understanding of the gospel, and equality among members. These communities are markedly different from what we observe in general society: they are not based on rigid rules, hierarchical orders, pre-assigned institutional roles, quality control of content, or positional ranks.

Instead, there is a palpable atmosphere where problems without clear centers can be resolved through the breath of the gospel. People experience an enthusiastic joy through being mutually connected in community life.

According to sociologist Pedro Demo in Sociological Problems of Community, modern sociology has moved beyond the traditional dichotomy that F. Tönnies described between society and community. Today, community is seen as a social formation of human beings adapted through mutual cooperation and a sense of belonging, while society is characterized by anonymous individuals and indirect relationships spread through popular trends. Demo states, “The relationship between community and society can be seen as if the community were a utopia within society” (p. 48).

Human togetherness always exists within the tension between “inhuman organization” and “deep human intimacy.” The issue of superiority within a community of equals is tied to the problems of preventing structural evil and enhancing real presence. The ultimate concern is how to humanize human existence and embody gospel values, drawing people into deeper intimacy with one another.

In a socially active society, even communities of equals tend to splinter into smaller groups. Therefore, the foundational Basic Christian Communities, which aim to recreate the church as an equal community, are essential. These communities represent a human community of equals within the larger social structure of the church.

Christianity, rooted in love, forgiveness, solidarity, rejection of oppressive power, and acceptance of others, stands against the hard, goal-oriented processes of individualism, selfishness, command structures, and rigid rule-following found in modern society. Instead, it is oriented toward new creation within a spirit of equal community and social structure.

Jesus called people into horizontal relationships—mutual respect, compassion, simplicity, and brotherhood/sisterhood. Vertically, He opened the way for sincere filial relationship with God—through simple, non-performative prayer and generous love toward God. Jesus had no interest in the organizational or institutional structures of humanity; rather, He emphasized the spirit of togetherness essential for life.

In the global context, the church stands on the same level as social and organizational structures. Within the church, there are both organizational elements that transcend specific communities and those that interrelate all communities. The authority of the church lies in this unity through love and hope. This is expressed in the confession of faith (creeds) that articulate fundamental unity in faith. There is also a global goal that addresses all local communities. The institutional framework (infrastructure) of the church can be truly renewed without distorting its historical essence or losing its traditional identity—only through the movement and impact of lay communities. The church that rises from the people is one and the same as the church that rose from the apostles.

The church can remain merely a religious institution within society, like any other social group. Alternatively, it can become a life-giving community that plays a creative role in nurturing and cooperating with all other communities in society—becoming a prophetic presence within and among them. When the church reclaims this prophetic mission, it will be able to bring God’s crown of justice to the cries rising from every corner of the globe. If not, it will become incomplete, professionally sterile, and ultimately, like the disciples who betrayed Jesus.

So then, what must be done for the foundation of ecclesiogenesis through Basic Christian Communities?

The basic community provides a vision of the church that stands in contrast to institutional structures—offering an eternal future. This does not imply an unattainable utopia, nor is it the only valid form of church structure. Rather, it seeks to revive the spirit of equal community and move away from bureaucratic, institutional images of the church—toward a space where members experience God’s presence through direct interpersonal relationships. This is not about eliminating existing congregations or replacing them. As long as they remain firmly connected to the whole church and continue ecclesiogenesis through mutual transformation and discipline, the church will avoid being fixed as a rigid institution and instead remain a living movement of faith—this is the true vision of God’s kingdom.

Three proposals may be studied further:

- The church community must move from an individual salvation mindset toward collective unity and action for human salvation. Only when the “I” participates in the collective historical creation of the “we” can a true social identity be formed.

- For the church to become a community of mutual service and sharing, it must embrace openness of belief systems, respect differing opinions, and maintain an attitude of equal dialogue that even includes those who have left. Broader perspectives and acceptance of new ways of life will allow for freer communication and fellowship.

- The church community exists within society. Since secular communities are in both direct and indirect relationship with the church, the church must actively participate in building the local community.

The process of ecclesiogenesis involves the formation of a conscientized, humanized, and generative community that resists the alienation caused by racism and sexism. This is the transforming praxis toward the true freedom, equality, peace, love, and hope that God desires.

[Notes]

1. A verbal interview was conducted with 13 women in intercultural marriages within the Embury Korean congregation to investigate the type of home environment they experienced during adolescence (ages 7 to 18). As of November 1991, the findings are as follows:

- Living arrangements during childhood:

- Lived with both parents: 1 person

- Parents divorced: 6 persons

- Lived with father only: 1 person

- Lived with mother only: 3 persons

- Lived with stepfather: 0

- Lived with stepmother: 5 persons

- Lived in an orphanage: 1 person

- Parental habits:

- Father was alcoholic: 8

- Mother was alcoholic: 2

- Father had gambling problems: 5

- Mother had gambling problems: 1

- Socioeconomic level of parents during upbringing:

- Upper class: 0

- Middle class: 1

- Lower class: 9

- Extremely poor: 3

2. Yang Ju-sam (Ed.). New Korean Language Dictionary. Seoul: Han-Young Publishing Co., 1975, p. 953.

3. Ibid., p. 954.

4. Webster’s New Universal Unabridged Dictionary, 2nd ed. New York: Dorset & Baber, 1979, p. 46.

5–13. The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, Vol. 1: Micropaedia, 15th ed. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1988, pp. 270–271, 6–10.

5. The New Encyclopaedia Britannica Vol. 1, Micropaedia, 15th Edition, Chicago, 1988, p. 270.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11. Ibid., p. 271.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid., pp. 6-8.

14. The concept of alienation, the foundation of all of Marx’s theories, is based on his early works, as explained by Erich Fromm in Marx’s Concept of Man (New York: Frederick Ungar, 1966). See also: Dirk J. Struik (Ed.), The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (New York: International Publishers, 1964); I. & C. Leroy Gaylord, “The Concept of Alienation: An Attempt at a Definition,” in Marxism and Alienation, ed. Herbert Aptheker (New York: Humanities Press, 1965).

16. T. Richard Snyder, Once You Were No People: The Church and the Transformation of Society, Meyer Stone Books, 1988, pp. 10–11.

17. Ibid., pp. 11-13.

18. Health Policy Advisory Committee. The American Health Empire: Power, Profits, Politics. New York: Random House, 1971.

19. Jonathan Kozol. Illiterate America. New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1985.

20. T. Richard Snyder, Ibid., pp. 13–14.

21. Ibid., pp. 14-15.

22. Ibid., p. 16.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid., p. 29.

25. Ibid., p. 33.

26. Ibid., p. 40.

27. The Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, ed. David Sills, Vol. 15. New York: Macmillan and The Free Press, 1968, pp. 618–621.

28. T. Richard Snyder, Ibid., pp. 43.

29. Ibid., p. 47.

30. Ibid., p. 49.

31. Ibid., pp. 50-52.

32. T. Richard Snyder, Once You Were No People, Meyer Stone Books, 1988, pp. 2.

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid., p. xv.

35. Ibid.

36. Richard J. Bernstein. Praxis and Action. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1971, p. ix.

37. Paul F. Knitter. No Other Name? A Critical Survey of Christian Attitudes Toward the World Religions. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1986, p. 193.

38. David Tracy, “Theologies of Praxis,” in Creativity and Method: Essays in Honor of Bernard Lonergan, ed. Matthew L. Lamb. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 1981, p. 36.

Also see:

- Lamb, “Dogma, Experience, and Political Theology,” Concilium, No. 113 (1979): 81.

- Lamb, “The Theory-Praxis Relationship in Contemporary Christian Theologies,” Proceedings of the Catholic Theological Society of America, 1979, p. 171.

39. Leonard Boff. Jesus Christ Liberator: A Critical Christology for Our Time. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1978, pp. 44–47.

40. Quoted in Rosemary Radford Ruether. To Change the World. New York: Crossroad, 1981, p. 27.

41. Bernard M. Loomer. “The Web of Life.” The Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA, October 1977, p. 1.

42. Allan Aubrey Boesak. Farewell to Innocence. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1977, p. 152.

43. Paulo Freire. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Ibid., p. 19.

44. Henri Bergson. Les Deux Sources de la morale et de la religion. Paris, 1932.

45. Karl R. Popper. The Open Society and Its Enemies, Vol. 1: Plato, and Vol. 2: Hegel & Marx. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1945.

46. Peter L. Berger. Facing Up to Modernity. Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy, 1977, p. 2.

47. Roy Bhaskar. The Possibility of Naturalism: A Philosophical Critique of the Contemporary Human Sciences. New York: Humanities Press, 1979, p. 27.

48. Demo. Article in Comunidades: Igreja na base, Estudos da CNBB, No. 3. São Paulo: Paulinas, 1975, pp. 67–110.