1. Approaching Transformation

Beginning the process of transformation to restore dysfunction in intercultural families is no easy task. Personal recovery through self-discovery becomes the first step toward an egalitarian community. Mental transformation becomes necessary when dysfunction has reached a critical level. Among Korean immigrant families—particularly women in intercultural marriages—numerous reports over the years have revealed severe dysfunction, including surprising cases of individuals exhibiting mental disorders. This does not necessarily indicate that there are more mentally ill individuals among Koreans compared to other ethnic groups. Rather, due to Korean cultural tendencies, families try every possible solution within the household. It is only when the problem becomes too severe to handle internally that they finally give up and seek external help—by which time, the condition is often extreme.

There are three key reasons for this pattern of problem-solving in Korean families:

- Lack of familiarity with Western concepts of mental health.

- A problem-solving style rooted in internal (introspective) effort.

- Fear of social stigma in a face-saving culture.

The process of becoming accustomed to Western ideas about mental health is very slow. In an unfamiliar society with different norms and behaviors, Koreans tend to label someone as “crazy” even when only minor symptoms of rigidity or dissociation are present. As a result, seeking help outside the family occurs only when family members are convinced that someone is truly “mad.” Many times, transformation could restore them to normal if intervention happened earlier—but families often miss this window.

Korean families fundamentally try to handle all problems within the family structure, seeing the act of exposing internal issues as shameful. This implies that the parents have failed to manage the household, leading to loss of face. Such strict secrecy prevents any softening of the belief that one has failed to meet the family’s expectations.

This leads to a third reason why Koreans do not seek help from professionals—fear of social stigma. In Korean immigrant communities, how a family is perceived by others is of great importance. This contributes to the challenges of immigrant life. In contrast, in American society, it is rare for people to sacrifice themselves or their families just to maintain their social standing.

There are three commonly cited causes for “mental illness” in Korean families:

- Hereditary traits within the family line.

- Perceived fate or destiny.

- The result of poor guidance or discipline by the family head.

Mental illness is often attributed to one or a combination of these factors. In any case, families seen this way often find it difficult to arrange good marriages, which are seen as vital to maintaining the family’s standing.

Because of these cultural factors, Korean families tend to rely on traditional or indirect healing methods—such as shamans, herbal medicine, natural diets, acupressure, breathing techniques, and even spiritual healing—within the household. As long as the family is not exhausted, they are reluctant to seek help from mental health professionals. When Koreans do turn to professionals, it is often in a state of shame and despair—after mental breakdowns, violence, suicide attempts, or total family burnout. In schools, when a student is found to have a mental disorder, schools may refer them to professionals despite family opposition. Still, even when individuals begin therapy, 53% drop out after the first session. Among the 48% who return, the average number of sessions attended is only 2.35.

Therefore, understanding Korean dialogue patterns is critical. Three components are key to conducting successful therapeutic conversations:

- Identifying the core issue

- Expressing emotions

- Navigating opposition

(1) Identifying the Core Issue

Before disclosing family conflicts or secrets to a professional, Korean families first attempt to build a sense of comfort and trust. They will not open up unless they feel the professional is on their side and trustworthy. At first, they may hide the true issue, showing only the tip of the iceberg or reporting something unrelated. Thus, it’s important to identify the hidden language in their words and behaviors and respond accordingly. When professionals detect subtle cues and patterns, families gradually feel safe enough to disclose more. This requires deep patience and the ability to read indirect signals and family dynamics accurately.

(2) Emotional Expression

Traditional Koreans exhibit emotional expression in a way that is completely different from Westerners. Sharing feelings openly in front of others may intensify tension rather than ease it. Expressions of love are not made publicly either. However, in showing affection toward infants or children, Koreans are often even more expressive than Westerners. Such early emotional experiences help children form deep and secure bonds. Once they become adults, love is not expressed through direct phrases like “I love you” but through indirect and concrete actions. For instance, a father working hard to provide for the family, offering guidance, and showing understanding is considered an expression of love.

This difficulty in expressing emotions causes challenges for Korean immigrant families raising children in the West. As children are exposed to media and Western peers, Korean parents may find Western parents’ affectionate and expressive attitudes toward their children both excessive and confusing. Koreans may even think Western children are misbehaved because their parents are “too soft” or permissive.

(3) Navigating Opposition

Expressing anger or criticism toward professionals, elders, or those to whom one is indebted is considered disrespectful. Therefore, younger or lower-status individuals refrain from expressing negative feelings to those of higher status. Even when they feel anger, they suppress or cautiously reveal it. Most of the time, these emotions are internalized, resulting in self-accusation or self-criticism.

2. The Basis of Transformation

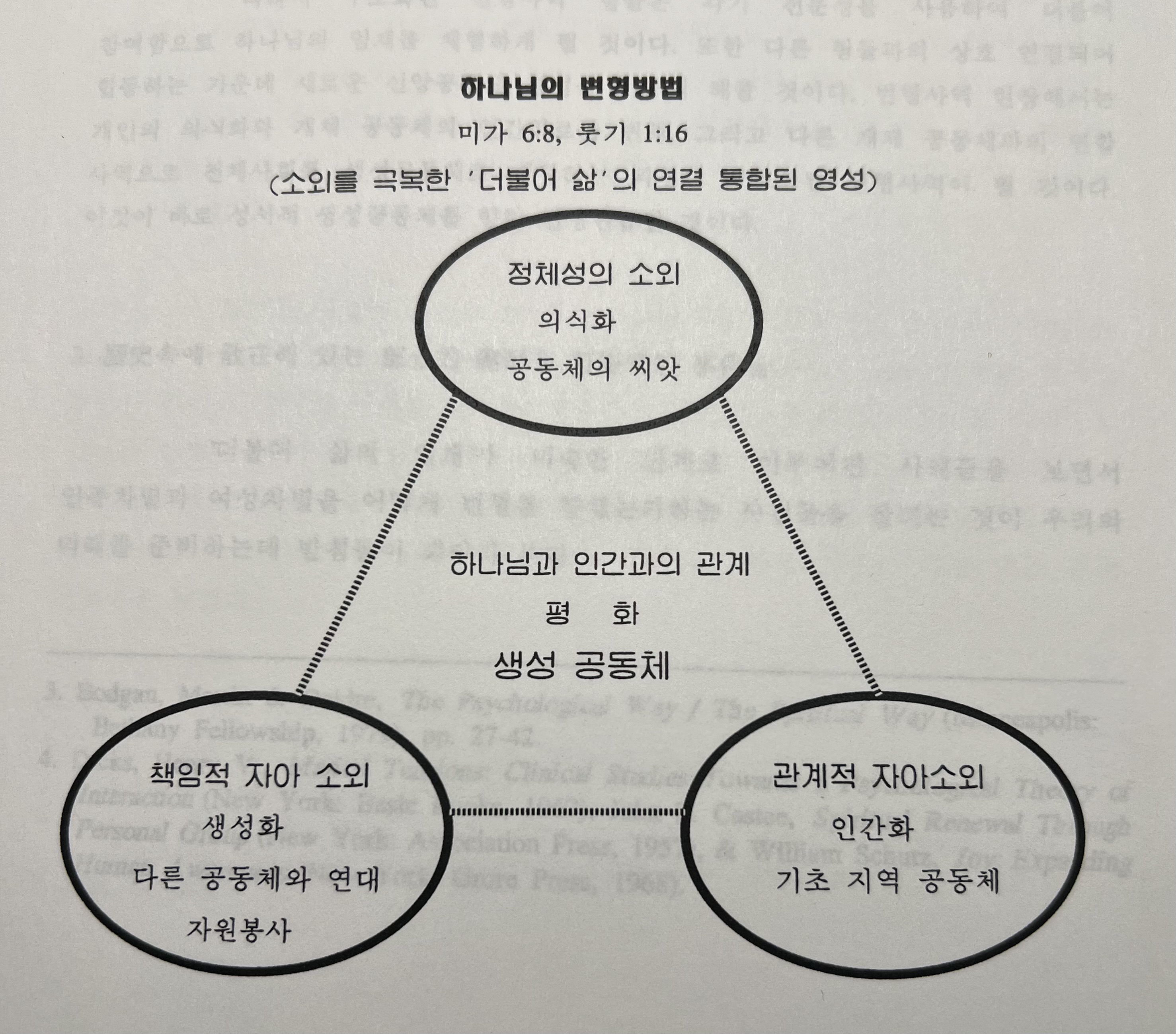

Transformation refers to a process that helps those who suffer from the loss of dialogue and experience alienation—defect, violation, distortion, or broken resolve—such as alienation from self-identity, alienation from the relational self, and alienation from the responsible self. Through a process of conscientization (awareness-raising), individuals rediscover themselves. When these individuals, having found their true selves, come together as authentic neighbors to form a humanized community, and when this community voluntarily works toward transforming society into a generative community, the entire process is called Transforming Praxis. Its goal is to restore people not just to their former state before illness or suffering, but to a more advanced, life-giving level. In this sense, transformation is one function of ministry.

Therefore, transformation ministry cannot be satisfied with merely returning a person to their pre-defect or pre-trauma condition. As a ministerial function, it is concerned with healing the body, psyche, and relationships—that is, the whole person.

Paul Tillich described transformation this way:

“Salvation is the fundamental and radical transformation.”²

He regarded human beings as a multidimensional unity, and emphasized that since dehumanization has already infiltrated every dimension of the human structure, transformation must be holistic. Transformation in only one dimension cannot bring about true healing or salvation.

Rather than focusing on the causes or mechanics of dehumanization, Tillich directed his attention to:

- the inner experiences resulting from dehumanization,

- the social problems that emerge in relationships with others, and

- the spiritual needs (conscientization) that arise because of it.

Thus, Tillich did not separate transformation from physical or mental illness, salvation from spiritual sin, or the challenges that occur in community life. In his view, when any single dimension of a person is damaged, it does not remain isolated—the entire person is placed in crisis. Therefore, true transformation is not merely the restoration of the broken part, but the recovery of the whole person.

In this light, the ministry of transformation begins with the conscientization of individuals suffering from alienation from self-identity, moving toward the formation of dialogical and egalitarian community. It then proceeds to the relational self, seeking humanization in the smaller communities where individuals live and suffer from alienation. Lastly, transformation expands to address alienation from the responsible self, encouraging voluntary service for the transformation of the entire society. Only when this layered and collective process unfolds can true and holistic transformation occur.

Jesus did not separate the body, mind, and soul in his ministry. He saw human beings as integrated wholes and ministered to individuals within their communities. Therefore, when Jesus liberated people from suffering, it was not just personal liberation—it was also communal liberation.³

Transformation Flowchart

+──────────────────────────────+

| ALIENATION FROM SELF‑IDENTITY |

+──────────────────────────────+

↓

Consciousness & self‑rediscovery

↓

+──────────────────────────────+

| ALIENATION FROM RELATIONAL SELF |

+──────────────────────────────+

↓

Humanization within small communities

↓

+──────────────────────────────+

| ALIENATION FROM RESPONSIBLE SELF|

+──────────────────────────────+

↓

Voluntary service for whole society's transformation

↓

→ Holistic transformation beyond pre‑illness state

As illustrated in the diagram on the front that depicts God’s method of transformation, human beings become truly whole individuals only when the structure of the whole is properly integrated. A defect in any single part inevitably leads to consequences that affect the entire person holistically. Even damage to a part of the natural environment results in suffering and illness for humanity, revealing the interconnected framework of “life together.”

In 1 Corinthians 12, Paul emphasizes that just as the body is composed of many members, each fulfilling its function, the suffering or honor of one member becomes the suffering or honor of all. Similarly, sociologists have demonstrated that everything about one member of a community is intrinsically connected with the others.

Therefore, the concept of transformation must be redefined—not as the change of a part, but as the transformation of the whole. When one part undergoes transformation, it remains interconnected with the whole, moving toward wholeness, and ultimately leading to a transformed, integrated, and generative community that overcomes alienation and lives in mutuality.

Accordingly, structured transformation ministry teams, each contributing their unique expertise, will experience the presence of God through mutual participation. Furthermore, through interconnection and collaboration with other teams, the formation of new faith communities will become possible.

In the field of transformation ministry, the structured process includes the transformation of personal consciousness, the humanization of individual communities, and collaborative ministry with other communities. All of these lead to the transformation of society as a whole into a generative community.

This is, indeed, the transforming praxis toward a biblical generative community.

3. Examples of Partial Healing in History

Examining cases in which early, incomplete structures of the “framework of life together” emerged—such as events that began to transform racial and gender discrimination—provides foundational lessons for preparing us for the future.

The Greek term amnesia means “forgetting the past” or “hindering memory.” In contrast, an-amnesis refers to restoring forgotten memories, collecting them once more, and embracing them as shared memory and hope. In other words, it’s a deliberate remembrance of past events.

In Deuteronomy 26:5–9, the Israelites are called to recall how God delivered them—a collective remembrance that gave them a sense of continuity and unity. Archie Smith calls this sense of shared hope in the present rooted in “anamnestic solidarity.”¹

1) Resistance to Viewing Women Only as Supporters

- Ann Hutchinson (before 1637) began to apply Paul’s teaching—“There is neither male nor female in Christ; you are all one”—in her life, hosting meetings in her home. She proclaimed spiritual equality publicly, gaining recognition even from men.

- Quaker women George Fox and Margaret Fell, founders of the Religious Society of Friends, argued that spiritual rebirth through the Divine Light applied equally to laywomen. Of the 55 early Quaker missionaries to America, 26 were women. Mary Dyer, influenced by Hutchinson, preached publicly in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and was eventually executed by hanging.

- During the Second Great Awakening, women were given new spiritual agency. Two-thirds of revival attendees were women, who testified to the Spirit’s work in their lives. Phoebe Palmer led revival meetings emphasizing spiritual gifts; Frances Willard, alongside Dwight Moody, served as an evangelist and led the Women’s Christian Temperance Union; Catherine Booth, wife of Salvation Army founder William Booth, became a powerful preacher. The theology of revival evolved into a form of liberation theology that challenged the idea of women as mere supporters.

- In 1895, Elizabeth Cady Stanton published The Woman’s Bible, prompting a reevaluation of scripture from a feminist perspective. Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza’s In Memory of Her further reinterpreted biblical texts, asserting women as active participants in the church.

2) Challenging the Concept of Women’s Inferior Status

One powerful example is Man-deok, a former gisaeng (courtesan) from Jeju Island:

- Born to noble lineage but sold into gisaeng status due to her mother’s early death, Man-deok later had her status restored and became a wealthy landowner.

- In 1795, Jeju Island suffered a devastating famine. Man-deok used her resources to buy and distribute grain, preventing a widespread humanitarian disaster.

- In recognition, the royal court exempted her from usual travel restrictions, arranged her reception in Seoul and at Mt. Geumgang, honored her publicly, and granted her a prestigious title.

- Afterwards, she returned to Jeju, built a temple, and became known as a Buddhist pioneer—her personal transformation inspired wider social renewal.

3) Confronting the Notion of Women as Idealists or Dreamers

In the Goryeo period, official Park Yu proposed allowing men to have secondary wives, arguing it would strengthen the state. When this suggestion provoked outrage, women openly protested—even spitting and hissing at his procession—forcing him into retreat.

During the introduction of Catholicism in the Joseon dynasty, many women embraced the faith despite harsh persecution. Notably, women outnumbered men among early martyrs, demonstrating fierce resistance to Confucian morality. They also practiced vows of virginity or celibacy, rejecting traditional marriages—an assertion of human dignity and theological liberty.

4. Church-Led Movements for Women’s Empowerment in Korean Diaspora

- Korean Women in Hawai‘i (1903–1945):

According to Alice Chai, these women not only fought to survive economically but also fostered solidarity in Korea’s independence movement. Central to their efforts was the church, which nurtured their identity, social networks, and political engagement. - National Council for Korean-American Multicultural Families (est. 1989, Colorado Springs):

Korean-American bicultural families within the United Methodist Church organized biennial retreats to foster community support. In 1994 they rallied nationwide to sign petitions for Ok Geum‑beon, a battered wife facing legal charges—mobilizing Christian women to advocate for her. - New York Asian Women’s Center (est. 1982):

Founded to address domestic and sexual violence in East Asian immigrant communities, operated by survivors and advocates. Services include multilingual hotlines, counseling, legal advocacy, and safe housing—with cultural sensitivity in education and prevention efforts. - Rainbow Center (New York):

A counseling center established in 1991 by pastor Yeo Geum‑hyun’s church. The church focuses on feminist biblical interpretation, recognizing the female divine and elevating women’s experiences in worship and culture. Since 1993, the center has assisted Korean immigrant women with housing, legal aid, counseling, and advocacy—culminating in major campaigns like “Free France” for Chong France’s release. - United Council for Korean ‘Comfort Women’ in Eastern U.S. (1994–95):

Following the UN’s 1995 Women’s Year declaration, this council organized protests, petitions, legal actions, documentary exhibitions, and lobbying—pressuring Japan to formally apologize and compensate former military sex slaves. - Manhattan Mission Center (mid-1990s):

Focused on outreach to Korean massage parlor workers in Manhattan, offering counseling, support, Bible study, and counseling services. The center received a church award for addressing domestic violence. - Korean‑American Women’s United Missionary Society (est. Aug 24, 1991):

Founded by the user, this society provides comprehensive support—spiritual, educational, emotional—to Korean-American bicultural women and their families. Programs have included AIDS support, prison visits, scholarships, and summer camps. By 1995, they had conducted multiple workshops, retreats, counseling sessions, and relief programs.

Before the reign of Daewongun, the powerful Andong Kim clan held sway even above the king, and Kim Jwageun stood at the pinnacle of that power. All authority converged on Gyodong, the residence of Kim Jwageun, who was the maternal uncle of King Cheoljong. Yet, even above Kim Jwageun stood another figure—his concubine, a courtesan named Nahap. Nahap was originally a kisaeng (female entertainer) from Naju in Jeolla Province, and she came from the same background as Geumun, the concubine of Lim Sang-hyeon, magistrate of Tongjin.

On Nahap’s birthday, Geumun visited her with a gift. At Nahap’s doorstep, no one dared raise their head, but Geumun boldly stepped up onto the wooden porch and declared,

“Human beings are born without distinction of high or low. You and I were both lowly kisaengs from the same house of pleasure, and by sheer chance, you came to serve the Prime Minister while I served a mere local magistrate. Even if we were to switch the men we serve, it would not be a disgraceful act. How then, can you teach even your nanny to behave with such arrogance?”

Geumun’s courage in this episode stands out as a rare and admirable instance of resistance in the long-suffering history of Korean women, where they have been stripped of their humanity like unfeeling stones. Her defiance can be seen as a pioneering gesture in the emergence of human rights consciousness during the Enlightenment period. Upon returning home, Geumun told her husband what had happened. He went to Kim Jwageun and apologized. But to protect her husband from political consequences and to assert her dignity, Geumun left his household, saying she could no longer serve such a man.

Later, during the Japanese invasion in the final years of the Joseon dynasty, many royal courtesans were expelled and left to wander the streets. Geumun gathered them together, offering them shelter and food, and actively pursued welfare work. Through personal connections in officialdom, she also secured grain to distribute to the women. She led an active and compassionate life and was revered as the “Mother of the Courtesans” until her death.

The nationalist consciousness of female students developed into a strong resistance movement for independence. One unforgettable event was the Short-Hair Donation by the Songjuk Secret Society at Sookmyung Girls’ School. This happened after Hwang Ae-deok, a recent graduate of Ewha Women’s College, became a teacher at Sookmyung. Along with fellow teachers Kim Gyeong-hui and Lee Hyo-deok, she agreed to secretly raise funds for the Korean Provisional Government in Shanghai by organizing a student resistance group. Every month on the 15th, the students gathered in the dormitory basement, each bringing 30 jeon as dues, and began with a prayer:

“We were born as women of this nation. Now we have discovered a task we can fulfill with our strength as women: to hasten the realization of our country’s independence. Lord, please do not withhold Your blessings from this mission. Enrich our hearts and our wisdom.”

Following the Song Society, the Bamboo Society was formed as a junior group by younger students. They raised funds by performing street acts such as birthday plays or singing vendor songs. Others embroidered traditional children’s headgear or waistbands, selling them to support the cause. Eventually, the members resolved to cut off their cherished long hair—the very symbol of feminine beauty—and sell it. This was a bold act of sacrificing part of their own bodies for the sake of the nation. It was a declaration of the timeless human value of freedom, beyond mere womanhood.

These stories are small but powerful examples of women who transcended the traditional concept of women merely serving men. I believe many more such “truly feminine” stories are scattered throughout history. For women, becoming conscious of the fact that they are not mere helpers to men is the path to reclaiming their humanity. At the same time, only when men transform their own misconceptions about women and come to recognize them as true companions can we hope for genuine female liberation—and for men’s own recovery of authentic humanity.

2) Cases of Resistance Against the Discriminatory Notion of Women’s Low Status

The following case illustrates how a woman, born into a low social class, came to embody a profoundly transformed and widely respected human figure. The impact of personal consciousness is immense. When the awakening of an individual’s consciousness becomes connected to the transforming praxis for the sake of community, it can act as leaven, changing a profit-driven society into a generative community woven through shared life. This story serves as a vivid example of such transformation.

Let us examine the resistance pattern of a Korean woman whose opposition to her lowly status blossomed into charitable service. A courtesan named Mandeok from Jeju Island did not know how she had become a kisaeng (courtesan), but later discovered that she had originally been born into a yangban (aristocratic) family. After her mother died early and with no one to depend on, she was registered in the gijeok (official register of courtesans). At the age of 20, she earnestly pleaded with the local magistrate to have her name removed from that register. Despite faithfully fulfilling her duties as a courtesan, she preserved her dignity and conduct with utmost discipline. Deeply moved, the magistrate ultimately removed her from the register and reinstated her as a commoner.

Once she returned to society as a free woman in the prime of her youth, she received many marriage proposals. However, Mandeok, disillusioned by the lethargy of Jeju’s men who lived off women, chose not to marry. Over the next ten years, she became one of the wealthiest single women on the island. In the 19th year of King Jeongjo’s reign (1795), Jeju was hit by a severe famine. Whole families in multiple homes were starving to death in villages across the island. The central government, in an effort to provide relief, requisitioned ships from the southern coast, crowding Jeju’s ports—but it was not enough to meet the need.

Mandeok used her wealth to purchase grain on the mainland and brought it to the port. With help from the local authorities, she organized a fair distribution system. First, she aided her relatives, then invited those suffering from starvation to gather in the large courtyard of Gwandeokjeong Pavilion, where she gave out food equally to all. Thanks to her intervention, there were no deaths by starvation until the next harvest.

The magistrate reported this to the royal court. The king was so impressed that he ordered all her wishes be granted. Mandeok requested a visit to Seoul and to Mount Geumgang. The government waived the Wolhaegeumbeop (the ban on Jeju women leaving the island) specifically for her, covered all travel expenses, and provided an official escort. Crowds of Jeju women came to the harbor to bid her farewell, while in Seoul, the Chief State Councillor Chae Je-gong personally welcomed her—an unprecedented honor for a woman from Jeju.

The king ordered the Seonhyecheong (a royal granary) to supply her generously, allowed her to be housed with female physicians from the royal clinic, and granted her the honorary position of Uinyeojang (chief of women physicians), which allowed her to enter the royal palace and have an audience with the king. In a royal decree conveyed through a lady-in-waiting, the king declared:

“It is deeply admirable that one woman’s righteous will saved 1,100 starving people during the famine.”

At age 58, while visiting Mount Geumgang, Mandeok encountered Buddhism and embraced it. Upon her return to Jeju, she established a temple and helped revive Buddhism on the island. As she departed from Seoul, government officials competed to offer her gifts, and noblemen of the capital gathered in front of the royal clinic just to catch a glimpse of her. Moved to tears, Chief State Councillor Chae Je-gong said:

“This life cannot be relived—how lamentable it is.”

This statement was a heartfelt expression of his desire to perform virtuous acts like Mandeok’s, rather than attain high political office. He later wrote The Tale of Mandeok (Mandeokjeon) in his collected works, and lamented:

“Though there are many ‘Man’ characters (meaning ‘ten thousand’ or ‘great’ in Chinese) in the world, not one is greater than this seemingly insignificant woman—how can this be?”

3) Cases of Resistance Against the Discriminatory Notion That Women Are Merely Dreamers

According to The History of Goryeo, a high official named Park Yu submitted a most controversial memorial:

“Our country already has more women than men, and we honor monogamy such that even men without sons hesitate to take concubines. But foreigners (from the Yuan dynasty) come here and take concubines without limit. At this rate, our talented men will all be absorbed into the north. I propose allowing government officials, high and low, to have concubines. If the sons and daughters born to these concubines could serve in office as legitimate heirs do, it would reduce public resentment, increase the population, and strengthen the nation.”

This petition represented one of the most severe crises for Korean women, essentially proposing a shift from monogamy to institutionalized polygamy. Yet, contrary to modern stereotypes, the women of Goryeo did not react passively or submissively. Historical accounts say:

“Upon hearing this, the women were enraged and could not contain their grief and fury. When Park Yu passed by in a palanquin, an old woman pointed at him and cursed, calling him a beggar who advocated for concubines. Other women spat and pointed at him. The backlash was so intense that some ministers, fearing the anger of their wives, did not dare return home.”

During King Jeongjo’s reign, despite the severe persecution of early Catholicism, many Korean women converted and embraced martyrdom with extraordinary bravery. In fact, more women than men were martyred, revealing that their desire to reclaim their humanity—repressed under the moral constraints of Neo-Confucian society—was even stronger than that of men. Among early Catholic women, a trend of choosing lifelong virginity emerged, even within marriage. Some women practiced “virgin marriage,” abstaining from physical relations with their husbands. These practices cannot be understood apart from the longstanding yearning of Korean women for freedom and personal integrity.

4. Movements for the Restoration of Women’s Rights Centered Around the Church in the Korean Immigrant Community

1) Korean Women in Hawaii (1903–1945)

According to Alice Chai, Korean women in Hawaii not only struggled for survival but also evolved into a united movement participating in Korea’s liberation cause. This serves as a powerful example of reclaiming their identity as women. These women developed economic networks, solidarity groups, and support systems to endure life’s hardships. Eventually, they grew into politically organized bodies striving to achieve their collective goals. All of this was centered around the often-invisible yet pivotal institution—the church.

2) National Association of Intercultural Family Ministries

In 1989, the National Association of Intercultural Families was formed by Korean Americans within the United Methodist Church during a gathering in Colorado Springs. Since then, a biennial retreat has been held for these intercultural families. It serves as a space for fellowship, mutual support, and strategic planning for ministry within intercultural family contexts.

In 1994, the association launched a petition campaign for Ok Geum-beon, a woman from Utah who was severely abused by her husband and, following a divorce, attempted suicide and took the life of her son, Joshua. Although she survived, she was charged with first-degree murder. Upon hearing of her case in October 1994, local women formed the “Committee to Save Ok Geum-beon,” submitting a petition (see Appendix D-2) to the presiding judge and initiating a nationwide Christian solidarity signature campaign via the national association.

3) New York Asian Women’s Center

Founded independently in 1982, this was the first center on the East Coast of the U.S. to address issues such as domestic violence and sexual assault among Asian communities. Staffed largely by women who had either suffered abuse or were deeply aware of such issues, the center operates in two major areas: direct service and structural change through education.

Direct services include a 24-hour multilingual hotline, counseling, legal advocacy, and safe shelters. Community education programs are tailored to the specific economic and cultural contexts of various ethnic groups. The center not only provides immediate aid but also works to improve the status of women in Asian communities, enhancing their quality of life.

4) Rainbow House (also known as Rainbow Women’s Center)

Located in New York City, this counseling center for intercultural families is affiliated with Rainbow Church, founded on September 29, 1991, by Pastor Yeogum-hyun. The church is rooted in a feminist theology that interprets the Bible from a woman’s perspective, affirms the femininity of God, and centers worship on women’s life experiences. The church’s mission includes resisting all forms of oppression against women.

Church programs include worship, fellowship, Bible study, small groups, home visits, leadership training, retreats, fasting prayer meetings, and lectures. To date, it has baptized 9 adults and 5 infants and supported seminary education for several members.

Rainbow Women’s Center, opened on May 15, 1993, has helped Korean women reconnect with families in Korea, find housing and jobs, receive confidential counseling, and support elderly parents expelled by children. It has also provided shelter to women traveling as far as Kentucky and Philadelphia in search of their children.

A notable achievement was the formation of the “Free France Campaign,” which fought for the parole of Ms. Chong France, imprisoned in North Carolina for the death of her son. This global campaign—mobilizing Korean churches, businesses, foreign newspapers, women’s groups, and U.S. churches—culminated in her parole on December 30, 1992, after two years of advocacy and letter-writing, including legal support from attorney Suh Seung-hye and local fundraising efforts.

5) Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery (Eastern U.S.)

Following the UN’s declaration of 1995 as the Year of the Woman, the World Council of Churches in February 1995 urged the Japanese government—not private entities—to resolve the “comfort women” issue that year. The International Bar Association and UN Human Rights Commission also joined in pressing for justice.

Activities in 1994 included:

- Efforts to block Japan’s admission to the UN Security Council

- International hearings involving seven victim nations

- Legal campaigns to identify and prosecute perpetrators

- Public awareness campaigns, including testimony collections, exhibitions by 1.5 generation Korean-American artists, and a full-page exposé in the New York Times

- A petition with 12,000 signatures submitted to Japan and the UN

Plans and actions in 1995 included:

- Launching a Comfort Women Research Center

- Exhibitions in New York, Beijing (World Conference on Women), and the Smithsonian

- Publication of English resources and newsletters

- Legal actions under international forced labor and human rights law

- Research and public outreach concerning survivors and perpetrators

- Representation in international human rights and women’s conferences

- Support for artistic productions related to the issue

- Outreach to 5,000 participants at the Beijing conference

- A $50 million fundraising campaign

6) Manhattan Mission Center

This center primarily serves Korean women working in Manhattan massage parlors, offering psychological and life counseling, Bible studies, and worship services. In March 1995, it was honored by New York Theological Seminary at a workshop titled “Church Responses to Domestic Violence.” The author of this text also led a workshop on the theology and biblical study of domestic violence.

7) Korean-American Women’s United Missionary Association

Founded by the author on August 24, 1991, the association aims to support underprivileged women from intercultural families. A brief history includes:

- Appointment to Embury UMC

- Founding of Hallelujah UMC (mostly Korean women from intercultural families) on Dec. 9, 1990

- Decision to form the association at the church general meeting on June 30, 1991

- Founding banquet held on August 12

- Official founding on August 23 with 19 charter members

- State accreditation for a technical school in February 1992

- Launch of personal Bible studies and counseling services

- First “Love Basket” campaign in December 1992, supporting 15 families

- Christmas party for homeless Americans on Dec. 25, 1992

- Ministry for a newly discovered AIDS patient in March 1993

- Reuniting a psychiatric patient, Ms. Lee Pil-soo, with her family in Korea in May 1993

- Sending 15 more women to live new lives of renewal

- AIDS patient passed away after accepting Christ

- Death of Timmer Jeong-ja in November 1993 due to tuberculosis

- Second “Love Basket” campaign to 24 families in Dec. 1993

- Monthly executive prayer meetings from January 1994

- Visit to Korean AIDS patient Mrs. Dexter in March 1994

- Prayer and education event on AIDS prevention in May 1994

- First Summer Camp for Intercultural Families in July 1994

- Launch of individual “professional psycho-spiritual transformation” sessions in August

- Charity concert in December 1994

- Scholarship recommendations and awards for children

- Prison visits in December 1994

- Planning of second winter retreat in Feb. 1995

- Mid-level spiritual formation workshops in June and August 1995

- October 1995: Introduction of volunteer training as part of women’s leadership training.

[Notes]

- McGoldrick, Monica, John K. Pearce, and Joseph Giordano, Ethnicity and Family Therapy (New York: The Guilford Press, 1982), p. 221.

- Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology, Vol. III (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967), pp. 11–29; 275–281.

- Bogdan, Martin & Deidre, The Psychological Way / The Spiritual Way (Minneapolis: Bethany Fellowship, 1979), pp. 27–42.

- Henry V. Dicks, Marital Tensions: Clinical Studies Towards a Psychological Theory of Interaction (New York: Basic Books, 1967); John L. Casteel, Spiritual Renewal Through Personal Group (New York: Association Press, 1957); and William Schutz, Joy: Expanding Human Awareness (New York: Grove Press, 1968).

- Archie Smith Jr., The Relational Self: Ethics & Therapy from a Black Perspective (Nashville: Abingdon, 1982), p. 21.

- Roger G. Betsworth, Social Ethics: An Examination of American Moral Traditions (Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1990), p. 161.

- Ibid., p. 162.

- Ibid., pp. 162–163.

- Ibid., p. 163.

- Lee, Kyu-Tae, The Consciousness Structure of Korean Women, Vol. 1: Are They Livestock or Human? (Seoul: Shinwon Publishing, 1993), p. 23.

- Ibid., pp. 30–34.

- Sixty-Year History of Soongui Women’s University.

- Lee, Kyu-Tae, The Consciousness Structure of Korean Women, Vol. 1: Are They Livestock or Human? (Seoul: Shinwon Publishing, 1993), pp. 25–29.

- Ibid., p. 17.

- Ibid., p. 24.

- Alice Chai, “Korean Women in Hawaii (1903–1945),” in Women in New Worlds, edited by Thomas and Keller (Nashville: Abingdon, 1981), pp. 328–344.

- New York Asian Women’s Center, 39 Bowery, Box 375, New York, NY 10002, Tel: 212-732-5230. & Appendix [D-2].

- Appendix [D-3].

- Manhattan Mission Center, Presbyterian Church for Korean Women, 110 W. 34th Street, Room 1100, New York, NY 10001, Tel: 212-268-4910.

- Yoon, Tae-Heon, Walking in the Light – Church Response to Domestic Violence (New York: New York Theological Seminary, March 3, 1995), unpublished workshop material. & Appendix [D-4].

- Appendix [D-5].

- Appendix [D-5-3~5].

- Appendix [D-5-7].

- Appendix [D-5-11~16].

- Appendix [D-5-26].

- Appendix [D-5-25].

- See p. 201.

- Appendix [D-5-17~18].

- Appendix [D-5-8].

- See pp. 208–209.

- See pp. 209–210.

- See pp. 214–215.